sábado, 27 de julio de 2024

A repressed love, and souvenirs from a wrecked ship: Tristan und Isolde at the 2024 Bayreuth Festival.

El barco de los recuerdos reprimidos: Tristán e Isolda en el Festival de Bayreuth 2024.

Streaming en directo desde el Festival de Bayreuth, 25 de julio de 2024.

Una vez más, celebro el aniversario de este blog, el séptimo ya, comentando la cita estival ineludible para cada wagneriano: el Festival de Bayreuth. Aunque será una celebración a medias, por motivos que pronto se revelarán. Mientras tanto, gracias al streaming, y a la televisión alemana, el mundo puede presenciar los estrenos de las nuevas producciones del Festival, haciéndolas disponibles para todo aquel wagneriano o melómano que no puede ir hasta la colina verde. Este año, la nueva producción es de "Tristán e Isolda", que junto al Anillo es la obra magna del maestro, y una de esas obras sin las cuales el rumbo de la historia de la música habría sido completamente diferente. Ya en 2022 se estrenó una producción de esta ópera, a cargo de Roland Schwab, que tuvo tanto éxito que convenció hasta a la ortodoxia wagneriana, pero de ella solo se dieron unas pocas funciones. La idea era tenerla como reserva en caso de que el Covid-19 impidiera representar la mediocre producción del Anillo que se tenía previsto estrenar, pero finalmente no pasó nada. En 2023 se dieron solo dos funciones de las que ni siquiera hubo emisión por radio, y mucho menos una emisión en streaming. Y así, aquella producción exitosa solo existe en fotos y audios para los desafortunados que no la vieron en el Festspielhaus.

Esta nueva producción corre a cargo del dramaturgo islandés Thorleifur Örn Arnarsson en la dirección de escena, y la orquesta está dirigida por el célebre maestro ruso Semyon Bychkov, reputado intérprete de esta ópera.

Es esta una ópera en lo que importa más lo interior que lo exterior: aquí lo que cuenta son los sentimientos de Tristán e Isolda, como si la música y sus monólogos fuesen la ventana a su mundo interno. De ahí la escasa presencia del coro y la escasez de personajes la mayor parte del tiempo. Por ello se presta no solo a ser muchas veces interpretada en concierto, sino a puestas en escena minimalistas, dado el carácter intimista de la obra. Ya en época de Cosima Wagner se intentaba reducir el atrezzo, para centrarse en la acción. Y en esta línea parece ir la puesta en escena de Arnarsson, minimalista la mayor parte del tiempo, y totalmente oscura, tenebrosa, como si los acontecimientos transcurrieran de noche, desde lo más recóndito del alma, contando la historia como una pasión reprimida y condenada al fracaso. No hay belleza, solo discreción y emociones, pero con un sentimiento de no hacer lo correcto.

El primer acto transcurre en un escenario vacío, solo hay unas cuerdas , e Isolda aparece con un enorme vestido blanco, un guiño al montaje de Jean-Pierre Ponnelle en 1983, totalmente lleno de palabras procedentes del libreto o de otras obras de Wagner. Isolda puede salirse de este vestido, dejando el miriñaque al descubierto, y al fondo, en la primera escena están Kurwenal, Brangäne y Tristán, como si estuvieran hilando el destino de Isolda (¿un guiño al Ocaso de los Dioses?). La entrada de Tristán en su confrontación con Isolda hace que se iluminen las luces. Tristán no bebe el elixir de amor, sino que antes de que pueda hacerlo Isolda lo tira. De hecho, aquí ese elixir no es otro que su enamoramiento, que el beso que se dan y con el que pasan a amarse apasionadamente.

El segundo acto es el más impactante, aunque la primera escena aún transcurre a oscuras. Es a partir de la entrada de Tristán, y el inicio de la gran escena de amor, cuando se ilumina la escena, para mostrar la enorme proa de un buque ruinoso, dentro del cual se encuentran un montón de cachivaches viejos, como relojes, maletas, documentos, un enorme globo terráqueo, y además algunos de esos trastos recuerdan a elementos de óperas de Wagner: una espada con la que Tristán se hiere la mano, un guiño al Anillo del Nibelungo, una estatuilla de un lobo, un guiño a La Valquiria, otra estatuilla, esta vez de una mujer medieval con un velo, un posible guiño a Tannhäuser, entre otros. Tristán no es herido por Melot, sino que bebe un elixir que lo envenena.

El Tercer acto es ahora ese mismo barco, pero despedazado, con todos los trastos viejos apiñados en un rincón, ahora Tristán lleva un mono gris con letras escritas. La amplitud que dejan los restos de ese barco vuelve a traer el minimalismo a la escena. Tristán muere, tras su larga y agónica escena, en la que una luz anaranjada atenúa la oscuridad. Isolda aparece, y tras ella los demás personajes, pero Melot no muere, y no se sabe, aunque se presume, que Kurwenal lo haga. Al final, Isolda canta su célebre muerte de amor, acurrucándose con su largo vestido, tras lo cual cae el lentamente el telón sobre un escenario bañado por una luz rojiza.

Semyon Bychkov regresa al frente de la Orquesta del Festival de Bayreuth tras dirigir Parsifal hace unos años. Tal y como ya lo hizo en Madrid el año pasado, Bychkov realiza una versión lenta, majestuosa, lírica, recreándose en la rica gama de sonidos y las posibilidades que puede hacer con la orquesta, para crear un mundo mágico, y al mismo tiempo profundo y melancólico, como este amor imposible. Majestuoso y bello fue el preludio, mientras que la introducción orquestal del tercer acto con el corno inglés es más introspectiva. La orquesta no tiene más comentario que su excelencia, con sus cuerdas, sus percusiones y sus potentes metales. Del mismo modo el coro masculino excelente en sus breves intervenciones del primer acto.

Andreas Schager, al igual que en el mismo Tristan que cantó con Bychkov en Madrid, se confirma como el Tristan del momento. Su timbre heroico, con toques juveniles, su resistencia al potente tercer acto, que cantó de forma arrebatadora pese a algunas notas que ya tiene que acortar, confirman lo anterior. Y a nivel actoral crea a un héroe solemne en el primero, como sensible en el segundo acto y en el tercero llega al culmen al recrear la agonía y alucinaciones del personaje.

Camilla Nylund, en cambio, no es una Isolda a su altura. La soprano finlandesa tiene una voz dulce, un timbre exquisito y un canto sensible, pero no es suficiente para Isolda. Si bien tiene momentos donde mejora, como en la segunda mitad del primer acto, la breve aria "Als für in fremdes land" en el segundo, cuando la voz requiere más agudo, el cual no puede durarle mucho, es donde le falla el volumen. De este modo, en el Liebestod no lograba imponerse a la orquesta. Y es una pena, porque en roles como Eva o Elisabeth ha sido notable.

Christa Mayer es una notable Brangäne, con una voz más firme que la de Nylund, excelente en su famosa canción de aviso "Einsam wachend in der nacht" en el segundo acto.

Olafur Sigurdarson es un Kurwenal bastante ligero, aunque en el tercer acto consigue salir adelante, debido a lo intimista de las escenas con Tristan pero falta más voz.

Günther Groissböck sufre de lo mismo, es un Marke exquisitamente cantado y tiene una preciosa voz que además tiene una dicción excelente, prueba del conocimiento que tiene de la obra. Sin embargo le falta más volumen y más grave en su largo monólogo del segundo acto.

Impresionante el Melot de Birger Radde, con una voz oscura, imponente, bien proyectada, tanto que él podría haber hecho un excelente Kurwenal. El resto de comprimarios, también, estuvieron a un buen nivel, marca de la casa: a destacar la voz lírica de Matthew Newlin como el marinero y Daniel Jenz como el pastor.

Una vez más, el elenco musical fue recibido con calurosos aplausos, sobre todo Schager, Groissböck y Nylund, aunque el más ovacionado, con razón, fue Bychkov. Abucheos, como todos los años, para el equipo escénico, aunque ya se sabe en Bayreuth: lo que se abuchea el primer año se ovaciona en el último. Tras esta función de estreno, queda inagurado el Festival de Bayreuth de 2024: un festival en el que hay más mujeres que hombres en el podio, y que se ha inaugurado con un bello Tristán, el cual confiamos mejore, sobre todo el elenco, en los próximos años.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.

domingo, 21 de julio de 2024

A pleasant, intense, beautiful return: Saioa Hernández sings Butterfly at the Teatro Real, first cast.

Madrid, July 19, 2024.

Saioa Hernández finally has the constant presence she deserves at the Teatro Real. In recent years, this soprano has sung there operas such as Un Ballo in Maschera, Nabucco, Turandot, and this year, Madama Butterfly. Montserrat Caballé, one of her singing teachers once stated that "she should sing in every opera house". Prediction fulfilled, since Hernández has sung on multiple European stages, mainly singing operas by Verdi and Puccini, being the most important Spanish soprano for this repertoire. At the Teatro de la Zarzuela, she sings every year, since our lyric genre is one of her great specialties. Aged only 45, she still has many glorious nights to offer us. As mentioned before, this year she sings Madama Butterfly at the Teatro Real, and she will do so in Barcelona by the end of this year. However, due to health problems, she had to cancel two of her seven scheduled performances, in order to recover and, with the professionalism that characterizes her, sing the last two, including last Friday's one.

Considering this health issue has been so recent, and despite this, Hernández has sung a beautiful and tragic Butterfly, in a shining portrait, despite the fact that her dramatic tone is now more suitable for roles such as Tosca, Turandot or Verdi roles than Cio-Cio-San. However, her portrait of this role is so convincing, so exquisitely sung, that she wins over the audience. Her smiles, Her gestures, their despair and her way of crying in the final scenes convey the moods, emotions of Cio-Cio-San, who despite all her suffering and her quick transition to adulthood, she is still much of a teenager.

From her entrance in "Ancora un passo or via" she surprised with a warm voice, a dramatic voice, but transmitting the candor of the character. Possibly they are still affected, but the high notes have som impact, as in "Amore mio" when Cio-Cio-San reveals she has changed his religion, and hugs Pinkerton. In the love duet, the warm, dramatic tone that we recognize in Verdi's operas makes it suitable for this piece. In the second act, the famous Un bel di vedremo aria was performed beautifully, in a sensitive, mature, dramatic rendition. In the scene with Yamadori, when she tells her what divorces are like in America, she is hilarious at imitating the judge and the husband who wants a divorce. And equally beautiful was the interpretation of "Che tua madre dovrà". Caballé's influence is noticeable in his way of intoning the bass, both in the phrase "sua grazia se ne va" and in "morta, morta", It is in this act and especially in the third one in which Hernández's voice feels more comfortable. Without a doubt, the best moment was the end, in the famous final aria "Tu, tu, piccolo iddio", where her voice sounded powerful, the volume surpassing the orchestra (when up to that moment there were some moments in which her voice was the surpassed one), showing her vocal power and her dramatic tone, which becomes so heartbreaking.

Matthew Polenzani has sung the brainless, despicable B.F. Pinkerton. This American tenor has a powerful voice, which can be heard, but the tone, which is intended to be lyrical, the higher the tone goes, the less pleasant it sounds. Even so, in the first act he was more inspired than in the third, although in the Addio Fiorito Asil, he began singing on the piano, something interesting considering Pinkerton's state of fear and remorse in that scene.

Lucas Meachem played Sharpless. The voice is good, it has an appreciable sound and a beautiful tone, showing experience, but he lacks some volume.

Silvia Beltrami was a wonderful Suzuki, with a beautiful voice and a beautiful velvety timbre. Her best moment was in the third act, with a resounding low voice in the heartbreaking words "Che giova? Che giova?" and a pianissimo in "Oh, me trista!", when she discovers Pinkerton's plans.

The rest of the cast, like the performance discussed on Sunday 15th, was at the same level, highlighting once again Mikeldi Atxalandabaso's Goro, with a stronger voice and a more confident projection than Polenzani's, the leading tenor.

Nicola Luisotti, conducting the Teatro Real Orchestra, was at the same level than on last Sunday, alternating powerfully conducted moments with ones more focused on just accompaniment. Again, the brass sounded like Wagner, in "Dite al babbo scrivendogli che il giorno del suo ritorno...", and then the brief concluding orchestral music sounded a little fast, depriving a bit from the power of the scene. The chorus is equally excellent, now highlighting the female chorus in the first act.

Little more to add about Damiano Michieletto's staging, I have already told everything in my last Sunday review.

The theater was not full, although it was more occupied than last Sunday. Tickets were even given to the Under-35 Friends of the Teatro Real, for free. However, despite this magnificent idea, the empty seats seen are not very comprehensible for such a popular opera like this. There were outstanding ovations for Meachem, and especially for Hernández, to whom the public showed their gratitude and affection. The last performance will take place tomorrow (July 22nd), to conclude a season in which we have enjoyed a triumphant spring dedicated to 20th century opera, with critical and sometimes even public success, to end it with a well-served Wagner's Meistersinger and now, a Butterfly with four casts of the highest international level. Now it is time to rest, from September on, the 2024-2025 season is waiting for us, with new emotions, with recitals by Flórez, Netrebko and Adriana Lecouvreur featuring Ermonela Jaho and Elina Garanča. Cannot wait!

Saioa Hernández en Madama Butterfly, primer reparto: intensa noche de ópera en el Teatro Real.

Madrid, 19 de julio de 2024.

Saioa Hernández tiene al fin, la presencia constante que se merece, en el Teatro Real. En los últimos años, la soprano madrileña ha cantado en el regio coliseo Un Ballo in Maschera, Nabucco, Turandot, y este año, el rol titular de Madama Butterfly. Una larga trayectoria la avala, así como la bendición de una de sus maestras, la gran Montserrat Caballé. "Debería cantar en todos los teatros" dijo la legendaria diva catalana. Predicción cumplida, pues Hernández ha cantado en múltiples escenarios europeos, principalmente cantando óperas de Verdi y Puccini, siendo la soprano española más importante en este tipo de repertorio. En el Teatro de la Zarzuela, canta todos los años, pues nuestra lirica es otra de sus grandes especialidades. Con tan sólo 45 años, aún tiene muchas gloriosas noches por ofrecernos. Como se ha dicho antes, este año canta Madama Butterfly en el Teatro Real, y a finales de este año lo hará en Barcelona. En estas funciones, figura en el primer reparto. Sin embargo, debido a problemas de salud, tuvo que cancelar dos de las siete funciones previstas, para poder recuperarse y con la profesionalidad que le caracteriza, cantar las dos últimas, entre ellas, la de esta noche.

Teniendo en cuenta que lo acontecido con su salud ha sido reciente, y pese a ello, Hernández ha cantado una preciosa y trágica Butterfly, en una creación que brilla con luz propia, aunque a priori podría considerarse que su voz ya no es la más idónea para este rol, sino para otros más complejos, sin desmerecer este. Y sin embargo, vive el personaje de forma tan convincente, con un canto exquisito, que termina por ganarse al público y resulta tanto o más auténtica que otras con la tesitura más adecuada al rol. Sus sonrisas, sus gestos, su desesperación y sus llantos en las escenas finales transmiten toda la montaña rusa de emociones que vive Cio-Cio-San a lo largo de la obra.

Ya desde su entrada en "Ancora un passo or via" sorprendió con una cálida voz, una voz dramática, pero transmitiendo el candor del personaje. Posiblemente aún se vean afectados, pero el agudo impacta, como en "Amore mio" cuando tras revelarle que ha cambiado de religión, abraza a Pinkerton. En el dúo de amor, el timbre cálido, dramático que reconocemos en óperas de Verdi, se deja sentir por todo el número. En el segundo acto, transmite la montaña rusa de estados de ánimo de Butterfly. El Un bel de vedremo fue interpretado de forma bella, una interpretación sensible, madura, dramática. En la escena con Yamadori, cuando le dice cómo son los divorcios en América, resulta divertidísima imitando al juez y al marido que quiere divorciarse. Es en este acto y sobre todo en el tercero en el que Hernández puede estar más cómoda. E igualmente bella fue la interpretación de "Che tua madre dovrà". La influencia de Caballé se nota en su forma de entonar los graves, en tanto en la frase "sua grazia se ne va" como en "morta, morta", donde a veces recuerdan a los de la catalana. Sin duda, el mejor momento fue el final, en la famosa aria final "Tu, tu, piccolo iddio", donde la voz sonó potente, imponiéndose a la orquesta (cuando hasta ese momento hubo algunos momentos en que ésta la sobrepasaba), mostrando su poderío vocal.

Matthew Polenzani ha interpretado a Pinkerton. El tenor estadounidense tiene una voz potente, que se deja oír, pero el timbre, que pretende ser lírico, no siempre es tan agradable, cuanto más al agudo se vaya. Aún así, en el primer acto estuvo más inspirado que en el tercero, aunque el Addio Fiorito Asil lo empezó cantando en piano, algo interesante teniendo en cuenta el estado de miedo y remordimiento de Pinkerton en esa escena.

Lucas Meachem interpretó a Sharpless. La voz es buena, tiene un sonido apreciable y un timbre bonito; además de notársele la experiencia, pero le falta volumen.

Silvia Beltrami fue una estupenda Suzuki, con una bonita voz y un precioso timbre aterciopelado. Su mejor momento fue en el tercer acto, con unos graves en las desgarradoras palabras "Che giova? Che giova?" y un pianissimo en "Oh, me trista!", cuando descubre los planes de Pinkerton.

El resto del elenco, igual que la función comentada el día 15, estuvo al mismo nivel, destacando una vez más el Goro de Mikeldi Atxalandabaso, con una voz más fuerte y una mision más segura que la de Polenzani, el tenor protagonista.

Nicola Luisotti al frente de la Orquesta del Teatro Real estuvo al mismo nivel, alternando momentos dirigidos de forma potente, con otros más de acompañamiento. De nuevo, el viento sonó como si fuera Wagner, en "Dite al babbo scrivendogli che il giorno del suo ritorno...", y luego el pasaje orquestal final sonó un poco rápido, lo que quitaba fuerza a la escena. El coro igualmente excelente, ahora destacando al coro femenino en el primer acto.

Poco más que añadir sobre el montaje de Damiano Michieletto, ya lo dije todo en mi crítica del domingo pasado.

lunes, 15 de julio de 2024

Madama Butterfly in present-day Japan: Damiano Michieletto's provocative staging at the Teatro Real.

Madrid, July 14, 2024.

Every summer, the Teatro Real closes its operatic season with an ABC repertoire opera. This summer, the chosen title is Puccini's Madama Butterfly, one of the most celebrated operas worldwide, which returns to the Teatro Real after seven years. Back then, it was sung by Ermonela Jaho and Hui He in the title role, and staged with the conservative staging by Mario Gas, premiered in 2002, in which sopranos such as Daniela Dessì, Isabelle Kabatu, Cristina Gallardo-Domas, among others, participated. Since its premiere at the old Teatro Real in 1907, this opera has been scheduled in several venues in Madrid throughout history.

Although today it is one of the most famous operas in the world, when it premiered at La Scala in 1904, it was a flop. Puccini made many revisions, more successful, until reaching the definitive one in 1907. Although he and his librettists Illica and Giacosa immortalized forever the tragedy of this Japanese geisha deceived by an American soldier, the story already existed previously. In 1887, Pierre Loti wrote "Madame Chrysanthème", based on his own experience: he married a Japanese woman with whom he lived briefly, after which the marriage was annulled, he returned to France and she remarried. In 1898, John Luther Long wrote "Madame Butterfly", based on an event that his sister experienced during a Christian mission in Japan, about a "tea house" woman abandoned by the father of her child. In 1900, playwright David Belasco turned it into a play, giving the plot its current form, which a moved Puccini saw it during a stay in London, after which he decided to turn it into the operatic masterpiece we know.

For this return, the Teatro Real has opted for a radical change, by choosing the Damiano Michieletto's raw, harsh, modern staging, which was premiered in Turin in 2010. Accordinf to Michieletto, this is not a love story, but the story of the exploitation of an impoverished teenage girl, by a Westerner who buys her sexual services. With the aim of focusing on the essence of this sordid story, the staging moves the action from the ancient Nagasaki in the Meiji Era, to the red light district of a modern and indeterminate Asian city. There are no fans, kimonos, tatami mats, geisha hairstyles, cherry trees or the port of Nagasaki with its green mountains in the background. Instead, the stage is occupied by blinding neon lights with female silhouettes, phrases in Asian languages taken from the libretto, and huge advertising banners showing hamburgers, closeups from very young women in suggestive looks, and manga drawings. In the center, a crystal booth that first represents a brothel and then Butterfly's house, stays. The impact of this production is, however, superficial. The concept may be interesting, an update of this story of a woman's purchase, but after a few moments of undeniable visual impact, it ends up becoming annoying, and even irrelevant, since the plot at least can be followed perfectly. However, there are moments such as the flower duo defacing the house by plastering it, or the child being almost dragged to the car, since this story wouldn't happen in today's Japan. In addition, the descriptive, exotic and colorful music of the first act does not match the slum seen on stage.

The curtain rises and we see a group of very young prostitutes (played by Asian actresses), dressed in very short clothes, walking around inside the booth, while a white car enters, from which Pinkerton and a group of friends come, ready for a night of partying. Goro, the matchmaker, in addition to being the pimp of the neighborhood, is a nasty ringleader who mistreats everyone, sowing terror among people. Cio-Cio-San makes her entrance in a modern blue dress. The wedding guests also wear colorful contemporary clothing. Afterwards, some street food carts provide them food, while the guests are sitting on ugly plastic seats taken from a dollar store, while street vendors offer their merchandise. Pinkerton is portrayed as a whoremonger (as if taken from the ending scene from the movie "Requiem for a Dream"), flirting with all the girls, before Butterfly appears. When he sings his famous aria "Dovunque al mondo", with the American anthem melody, one of the advertisements rises to display images of the Marines and other American soldiers on various missions around the world. Uncle Bonzo appears in a wheelchair to curse his niece. In the love duet, Butterfly appears most of the time singing from the roof of the booth, while Pinkerton responds to her from inside, which are not very ideal conditions for a passionate love duet.

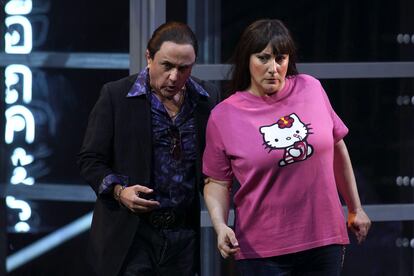

In the second act, we see Butterfly climbed back onto the roof of her booth at the very beginning, now dressed in her now iconic pink Hello Kitty t-shirt, jeans with butterfly decorations, and white sneakers. Inside the shed there are a variety of toys lying around and disorganized. There are huge puddles around the house, indicating that Butterfly is still living in destitution. Meanwhile, under the big banner, the young prostitutes and Goro take photos; one of them is dressed in blue, heading to her wedding, to meet a buyer husband (an indication that the story always repeat itself?). Prince Yamadori comes on a modest motorcycle, and he is a well-dressed old man who comes with gifts, inside two horrible raffia bags. A moving, but at the same time eerie moment is when Consul Sharpless reads the letter to Butterfly, the lights go out, and while he is reading, Pinkerton himself appears to cuddle Butterfly, as if in a recreation of her illusions. When their son appears, he is an older boy, so it seems that more than three years have transcurred, since he comes with his school backpack. Butterfly and Suzuki do not decorate the house with flowers, instead they daub the glass walls with tempera paints, drawing shapes of flowers and hearts.

During the famous humming chorus, Butterfly and Suzuki leave the boy sleep inside the house alone, while the prostitutes appear carrying lights to put inside the room, and then turn them off. When the famous orchestral Intermezzo begins, the boy wakes up and plays with some paper boats in one of the puddles, until other children appear, to bully him by throwing his own, wrecked boats at him: the blonde boy with asian blue eyes is despised in the neighborhood. When the interlude ends, Suzuki and Butterfly prepare him for school. The white car appears again, from which Pinkerton, Sharpless and Pinkerton's wife, Kate, get out, dressed in a luxurious but tacky way, giving her the image of an unreliable woman. Pinkerton's moral misery is reflected in the fact that during this scene, he gives Sharpless some dollars to compensate the poor Butterfly, but he throws them away. Even his own wife is disgusted. During the tragic final scene, Butterfly tries to kill herself by stabbing herself, but gives up when she suddenly sees her son coming from school, to whom she says goodbye in her tragic final aria. Then, while the boy is playing on a swing, she commits suicide by shooting herself, and Pinkerton immediately appears to forcibly take the boy and put him into the car, since he does not want to follow him. The curtain falls with Butterfly dead, alone, lying on the floor.

Puccini's music describes an idyllic atmosphere, with its playful melodies, of oriental inspiration in the first act, to move on to the most absolute and moving drama in the remaining two. The Teatro Real Orchestra is again conducted by the maestro Nicola Luisotti. But despite moments of brilliance, the conducting has resulted somewhat between correct and routine. In the middle of the first act it reached a nice rendition, with the wind and percussion recreating that idyllic oriental world that does not correspond with the staging. There has been some spectacular moments, such as the orchestral tutti as in "Dite al babbo scrivendogli che il giorno del suo ritorno, gioia mi chiamerò" or in the powerful finale, although the orchestral interlude between the second and third acts was not as spectacular as it should have been. wanted. Mention for the violin in the letter scene, and for the cello in the third act. The Teatro Real Choir, in its brief interventions, at the always good level, shaking in the first act with the phrase "Ti rinneghiamo!", totally piercing, which resonated in the hall. Their performance in the famous closed-mouth chorus of the second act is moving.

Lianna Harotounian says goodbye to Madama Butterfly after singing this role for a decade. This Armenian soprano adapts perfectly to the tessitura: her voice is able to be sweet, candid, dramatic and powerful (just as she did in her Desdemona and Trovatore's Leonora in past seasons) when required. This is convenient in this opera since in the first act, Harotounian sings with a childish and tender tone, showing fragility and candor in this act. In the second act, this tone alternates with a more dramatic one, a reflection of the character's maturity. The treble remains firm and well projected, and the low voice is heartbreaking in phrases like "morta, morta" in Che tua madre dovrà. At an acting level, she conveys the emotions of the character, in a convincing portrait of this lonely and abandoned mother.

Michael Fabiano, who in three years has sung the four main Puccini tenor roles in Madrid, has been a remarkable and very enjoyable Pinkerton. Although his voice is more mature, his vigorous tone and vocal resistance and stamina continue to confirm him as one first choices for this repertoire. Throughout the first act he shows a vigorous,heroic voice with a youthful, gallant touch. The singing is powerful in "Bimba dagli occhi pieni di Malia". In the third act he maintains the level, with a beautiful version of "Addio Fiorito Asil".

Gemma Coma-Alabert was a correct Suzuki, a very good actress, in her role as matron protector of Butterfly and her son, with a notable low voice in the third act. Gerardo Bullón is a correct Sharpless, who was very good in the first act, and correct in the remaining two, although with a moment of brilliance in the letter scene. It is always to hear again the Basque tenor Mikeldi Atxalandabaso, now in the role of the unpleasant matchmaker Goro. His excellent character tenor voice is suitable for his convincing performance as a brutal and feared pimp. He is, without any doubt, one of the best spieltenors today. Fernando Radó was a correct Uncle Bonzo. The rest of the cast was at the same level.

Although many people the audience did not agree with the staging, everyone enjoyed a good opera evening, noticed in the final ovations for Fabiano and Harotounian. The hall was not fully occupied, maybe because of holidays, or even the Euro Cup final football match, which Spain won last night, winning its fourth cup. Still, Madama Butterfly has such capacity to delight and move that it is always a pleasure to watch. These performances are being dedicated to Victoria de los Ángeles, a legendary Butterfly, having different memento, gowns and kimonos displayed throughout the theatre, in contrast to the Hello Kitty t-shirt that tonight's Butterfly wore.

Historia de una mujer comprada: Madama Butterfly en el Teatro Real, tercer reparto.

Lianna Harotounian se despide de Madama Butterfly tras cantar este rol durante una década. Esta soprano armenia se acomoda perfectamente a la tesitura: su voz es capaz de ser dulce y cándida cuando debe, y dramática y potente (tal y como hizo en sus Desdémona y Leonora de Trovatore en este escenario) cuando se le requiere. Ello es conveniente en esta ópera ya que en el primer acto, Harotounian entona como una cría, con un timbre aniñado y tierno, mostrando fragilidad y candor en este acto. En el segundo acto, se alternan por momentos este timbre y luego uno más dramático, reflejo de la madurez del personaje. Los agudos siguen siendo firmes y bien emitidos, y el grave desgarrador en frases como "morta, morta" en Che tua madre dovrà. A nivel actoral transmite las emociones del personaje, dentro de lo que le permite el montaje, pero resulta creíble como esta madre sola y abandonada.

Michael Fabiano, quien en tres años ha cantado en Madrid los cuatro grandes roles puccinianos para tenor, ha sido un notable y muy disfrutable Pinkerton. Aunque la voz está más madura, el timbre vigoroso y su resistencia vocal siguen convirtiéndole en una de las primeras opciones para Puccini. Durante todo el primer acto da una muestra de vigor, con su voz heroica con un toque juvenil, galante. La voz resulta potente en "Bimba dagli occhi pieni di Malia". En el tercer acto mantiene el nivel, con una bella versión del "Addio Fiorito Asil".

Gemma Coma-Alabert fue una correcta Suzuki, muy buena actriz, en su rol de matrona protectora de Butterfly y su hijo, con un grave notable en el tercer acto. Gerardo Bullón un correcto Sharpless, que estuvo muy bien en el primer acto, y correcto en los dos restantes, aunque con un momento de lucimiento en la escena de la carta. Magnífico una vez más el vasco Mikeldi Atxalandabaso, ahora en el rol del desagradable casamentero Goro. Su excelente voz de tenor de carácter y su convincente actuación como un alcahuete brutal y temido fue convincente. Cumplidor Fernando Radó como el tío Bonzo. El resto del elenco estuvo en un correcto nivel.

martes, 2 de julio de 2024

A static, charming fairy tale: the Werner Herzog's 1990 Lohengrin in Bayreuth.

Traditionally, Lohengrin has been performed either as a tragedy (Wagner's only one) or as a fairy tale. Herzog chooses this way. The famous filmaker choses aesthetics which are reminiscent of romantic paintings, such as those of the painter Caspar David Friedrich. The first act takes place in a gray landscape, dominated by two leafless trees, snowy, or swampy. Lohengrin appears in a magical aura of radiant blue beams. The second act takes place at night, with a starry sky and a big moon, in what appears to be the ruins of an ancient church, on the shore of the sea, which is recreated with real water. In the second half of it, the procession, which was asleep behind, wakes up to the sound of the trumpets that announce the dawn, and the image of a big Gothic cathedral is projected in the background. The third act takes place in an idyllic landscape, a green meadow, the marital bed is a bed with a silver swan, surrounded by rocks (Herzog wanted to surround the Festspielhaus with rocks, in a sort of pagan ambiance, but Wolfgang Wagner said no), in what seems like a pagan ritual, syncretized with the religious world of Lohengrin and Elsa, presided over a dense navy blue sky. At the end of the opera, Gottfried is a half-naked boy, with his body painted white and wearing the head of a swan. As Lohengrin leaves, it begins to snow, everyone becomes distressed, and in an unexpected gesture, Elsa and Ortrud shake hands, possibly forgiving each other or sealing a new alliance.

Henning von Gierke's costumes are simplified, discarding armors, opting for simple colored tunics, except for the antagonist couple, who wear stiffer suits, him wearing wolf coat, a nod to tribalism, and she wearing an intense red big dress. However, if the staging has beautiful costumes and sets, depicting a fairy tale world, it loses quality in acting, since there is not much movement on stage, the chorus and soloists adopt a static, sometimes almost motionless positions, moving quite little. There are inspired moments, such as Ortrud's look of rage in the second act when Telramund reproaches her for her misfortune, or Elsa's angelic expressions when she sees Lohengrin or when listening to his famous story from the last act. It is surprising that a famous film director chose not so much movements on stage, something more typical of productions of the past, when the artists stood on the stage and just sang. Like the Schneider-Siemssen's stagings at the Levine's Met, it is the artists who let their expressions to flow freely, conveying their own portrayals of the characters by mostly their singing.

However, in musical terms, if this recording has a singularity, it is that it is Peter Schneider's recording legacy for all time. This German conductor has been considered a "rutinier", someone who knows the work, has experience, who gives more or less reliable interpretations but they do not become mythical, sometimes not even notable or just mere accompaniment. However, conducting the Bayreuth orchestra, and with an excellent sound recording, Schneider manages to make the miracle happen, achieving one of the most beautiful versions of the orchestral preludes, in the entire discography of this opera. The orchestra sounds spectacular, more lyrical, more fairy tale-like, more angelic than passionate and dramatic, something that must have helped the cast on stage, since the rendition seems to have been respectful to their voices' volumes. Although in the third act the tempi do slow down a little, the level does not drop too much in what is a sublime orchestral direction. Schneider was at the peak of his career in those days. The Chorus as usual, excellent, brilliant in its great scene in the second act or in the wedding march from the third act.

Cheryl Studer's rendition of Elsa is, apart from Schneider and Herzog, the other great peak of this recording. With her beautiful voice, with such a sweet and lyrical tone, she is one of the greatest Elsas of recent decades. His interpretation of Einsam in Trüben Tagen is pristine, angelic, in the level of the greatest singers of this role.

Paul Frey did not get so many good reviews with this Lohengrin. His entrance in the first act is very good, but in the rest of the work, although he maintains the considerable volume and heroic tone, the performance does not stand out too much.

Ekkehard Wlaschiha, with his powerful voice and dark, villainous tone, is the main male voice, with an excellent performance as Telramund.

Gabriele Schnaut, with her distinctive timbre, is a remarkable Ortrud, with a tone somewhat lighter than a dramatic Varnay or Meier, which suggests a young but scheming, evil profile of this role, her high-pitched tone, and her powerful voice merge with an imposing stage presence.

Manfred Schenk, a light bass, has a devoted singing, but a just correct tone for King Heinrich, as well as Eike Wilm Schulte as the Herald.

Even with its ups and downs, this is a remarkable and extremely beautiful Lohengrin. Totally recommended, especially for lovers of classic stagings and beautiful aesthetics, and for those who prefer the fairy-tale approach to this romantic opera.

:format(jpg)/f.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F62a%2F05a%2F48d%2F62a05a48d588387b24c4ccd44255c5f8.jpg)