Madrid, December 26, 2025.

If I were to discuss the worldwide fame of the Carmen myth, one of the most famous associated with Spain, I would have to point out a double irony: that this myth, so embraced by us Spaniards, is the work of two Frenchmen, Mérimée and Bizet; and the fact that France's most famous opera is based on an invented, exotic, and stereotypical story about its neighboring country, rather than on any of its own popular stories or myths. Considering the strong antagonism that has always existed between both nations, and which still persists, this is a very odd cultural link between them.

And there she is, that untamed gypsy, captivating the world, one hundred and fifty years after the premiere of the opera that catapulted her into universal culture. Merimée created a wicked charismatic character, with a fatal charm, a liar, a skilled manipulator, in his novel. Bizet softened these characteristics, transforming Carmen into a woman incapable of forming a stable, monogamous relationship, unaware of the fatal consequences of her charm, even if she has to use it for her own goals, but at the same time she is also someone who proclaims her emotional and sexual freedom, in an era when the "decent" woman was expected to be rather obedient and virtuous. In her time, she was an example of a she-devil. Today we see her as someone who raises her voice, stands for herself and who doesn't allow anyone to do whatever they want with her. In contrast, Don José, seen in his time as a poor man who falls into the hands of a wicked woman who brings out the worst in him, is now seen as a toxic, possessive, immature, chauvinistic, repressed man, incapable of handling the consequences of his unhealthy love for this woman. Furthermore, following the conventions of the opéra-comique, Bizet and his librettists Meilhac and Halévy added the romantic figure of Micaëla, a virtuous young woman in love with Don José, as a counterpoint, and gave greater prominence to the bullfighter, here called Escamillo, Carmen's new lover, who is aware that his relationship with her is merely an affair.

At this time of year, the capital is immersed in a whirlwind of Christmas lights, crowds buying presents, as well as food for Christmas and New Year's Eve, and the theaters are overflowing with their vast array of entertainment. And every year around this time, the Teatro Real programs a popular opera to boost its revenue: now it's the turn of Carmen. Twenty-three years ago, also for Christmas, this opera was also staged at this same venue, being the first time I saw it live. Alain Lombard conducted it, and Denyce Graves and Béatrice Uria-Monzon (whom I saw) alternated in the role, and the staging was the classic and spectacular one, with lavish costumes, sets and corps de ballet, by Emilio Sagi (which had premiered in 1999 with Agnes Baltsa as the gypsy). In 2017 this opera was staged with the celebrated production by Calixto Bieito, which remains the benchmark modern production today. In 2024 it was performed in a concert version, with René Jacobs offering the original version composed by Bizet before the arrangements for the premiere.

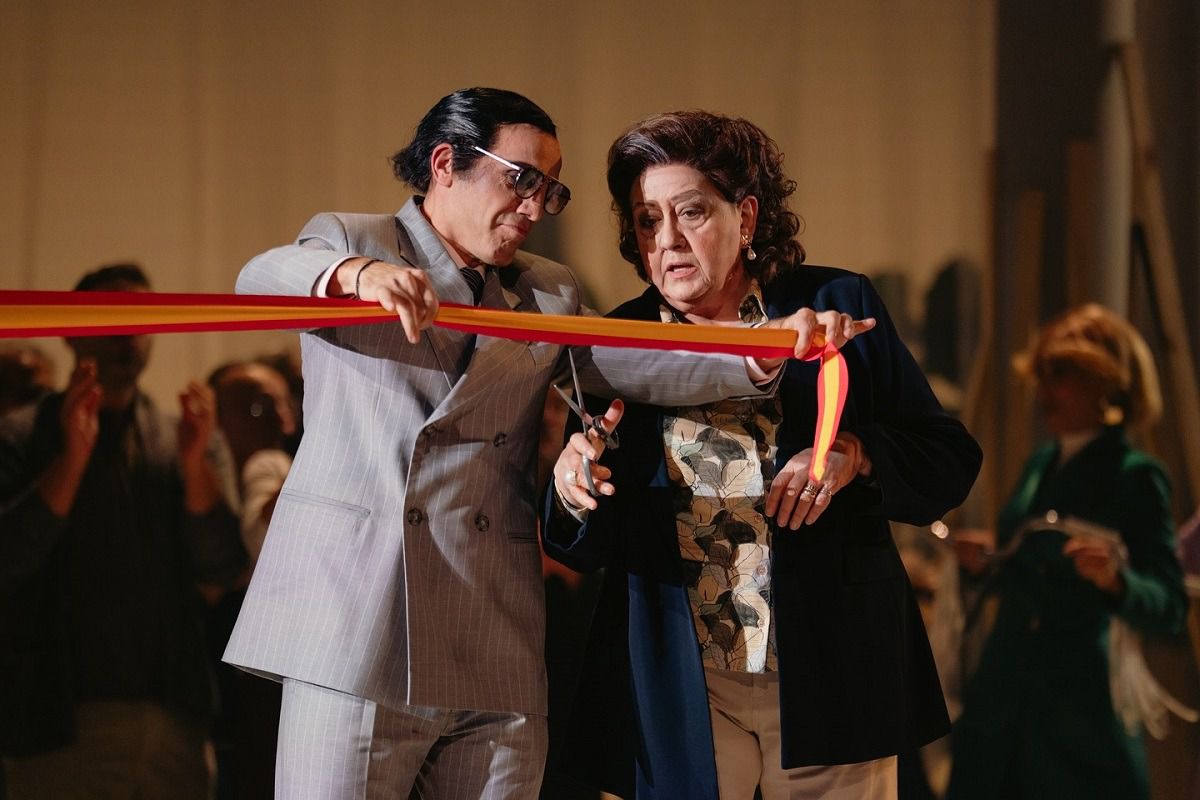

This time, the production was directed by Damiano Michieletto, from London. Michieletto previously directed a beach-set Elisir at this theater years ago, and last year a somber Madama Butterfly. Watching this production, one can't help but think of Bieito's, as it owes a great deal to it. There are even moments that seem almost identical, such as the appearance of vehicles and the circular turning sets, or the chorus dancing in its grand scene in Act IV. Michieletto seems to have transposed the action to the 1970s, in a desert landscape, in a Hispanic and presumably developping country, which could be post-Francoist Spain, or even Mexico, to which I find it more similar. In a presumably conservative society, the production takes the supernatural, which is important for the protagonist, and reincarnates it in Don José's mother (played by actress Lola Manzano), a character not present in the original opera. She is a woman dressed in black with an enormous mantilla, a severe and possessive figure, who appears during moments of tension and explains the protagonist's insecure, inmature personality. This isn't entirely successful, since when Micaela tells José in the third act that his mother is dying, how can we explain her appearing in the fourth act, robust and as if nothing had happened? Another important point is the stark contrast between Carmen and Micaela: the former aggressive and sensual, the latter portrayed as a prudish young woman, modestly dressed, only lacking brackets to resemble ABC's Ugly Betty. This explains why, when Morales says in the first act, "Que cherchez-vous, la belle," it doesn't seems real. Once again, with Michieletto, the change of era seems interesting, even some few details can be remarked, but at the end it becomes irrelevant because the plot is easy to follow and one can overlook such ugliness on stage. Furthermore, there are no recitatives between the musical numbers, and dialogues have been reduced to a bare minimum.

In the second part of the prelude, when the theme of fate is introduced, José's mother appears, showing the letter of death, which she will later show to Carmen. The first act takes place, as mentioned, in a desert landscape, dominated by a police station with a sign in capital letters that reads "Policía Local (Local Police)" The stage rotates, revealing the interior of the station, with a table on which sits a typewriter. At the end of the act, a voice is heard saying something like, "José, when your destiny is fulfilled, you can come back to me; I am old now." It is the mysterious voice of the domineering mother. The children have a more prominent role than in the original, since during the interludes they tell us, using cardboard signs with red letters, how much time has passed: a month later, at the beginning of the second act; the night after, at the beginning of the third one ; and a few days later, at the beginning of the fourth. So, there is another failure: Carmen and José have only been (slept) together for one night, which isn't enough time for her to get tired of him, too soon considering she is so infatuated, and conclude that a life of crime isn't for him. Or for José to finally tell her how much they loved each other once ... just a week ago.

At the beginning of Act II, and with no Lilas Pastia due to the supression of dialogues, the police booth is replaced by a seedy disco, where Carmen dances with her friends and with Dancaire. Even Frasquita joins doing twerking. At the end of the act, José's angry mother throws the flower he gave to Carmen, to the ground. In Act III, a van appears, from which Zúñiga is pulled out with his head covered, while smugglers point a gun at another soldier. The booth is now a warehouse, from which, during her aria, Micaela pulls out a rifle and defends herself against the smugglers. During the interlude of Act IV, a man is shown knitting Escamillo's jacket, and being bothered by the children. The booth is now a luxurious dressing room where Escamillo gets ready; there are mirrors and photos of other bullfighters. Around her, the chorus celebrates and dances while buying hats and fans from a street vendor. Everyone asks the bullfighters for autographs, and children sneak into Escamillo's dressing room to do so. During the final duet, a green light intensifies the scene, and José doesn't stab Carmen, but strangles her, in the presence of his mother.

The Teatro Real Orchestra was conducted by Eun Sun Kim , whose performance was uneven: the orchestra began with great energy, and also a lot of volume, with a rather fast prelude... the opening of the first act had a rough sound in the strings. However, from the third act onwards, while the sound became more balanced, the conducting went into slower tempi. I venture to say that the best orchestral moment was the interlude before the third act, which would have benefited from a slower tempo, and in which the flute shone. The cellos also had a beautiful sound playing Escamillo's motif when he leaves the stage in the third act. The Teatro Real Chorus improved as the performance progressed. After a first act in which they were still finding their rhythm, they shone in the second and third acts, again striking at the end of the second, closing the scene with a powerful "La liberté." In the third act, they were equally good in their well-known opening number. The Children Choir (Pequeños Cantores de la ORCAM) , with more girls than boys singing, improved in their singing as the performance progressed. And along with the other child actors, they stole the show in their appearances.

Aigul Akhmetshina is arguably the Carmen of our time. The young Russian mezzo-soprano is also acclaimed by the Teatro Real audience after her brilliant performance as Elisabetta in Maria Stuarda a year ago. Musically, she is enjoyable and remarkable. She is at her peak, and her Carmen features a velvety voice, a dark timbre, with which, at least musically, she conveys the sensuality of the character. The seguidilla and the gypsy song are two great examples of this. She also has a beautiful low register, as demonstrated in the card aria in the third act. As an actress, she is remarkable; she knows how to be as sensual and captivating as the character, despite her imposing physique. But the latter is actually the least important thing, comparing to her beautiful singing. In my very personal opinion, she is the best Carmen I have seen live since Uria Monzon and Graves (whom I saw in 2005 in a staging at the Madrid bullring).

Adriana González is an excellent Micaëla. Although the staging doesn't do her character justice, her voice is so charming. A lyric-timbred, but with a more dramatic. And in the duet with José and in her aria, she delivered a couple of very beautiful pianissimos.

Charles Castronovo 's Don José is a mixed bag. His voice isn't bad, but it has its ups and downs: in the second act aria, he does his best, and his best performance is at the end of the third act, where he shines vocally in the high notes and convincingly portrays the audience with his sobs when Micaela tells him his mother is dying. In the final duet, however, his voice seems tired, being overshadowed by Akhmetshina's presence.

In contrast, Lucas Meachem showed more voice as Escamillo, and stage presence is also greater than Castronovo's.

Of the rest of the cast, special mention must be made of the always noteworthy Natalia Labourdette, here in a beautifully sung (what a delightful timbre!) and acted Frasquita, far superior to Marie-Luise Chappuis's Mercédès. The always excellent spieltenor (the leading one in Spain) Mikeldi Atxalandabaso was a well-sung Remendado in his very brief appearances.

As with so many popular operas, Carmen's performance run at the Teatro Real is always sold out. This one was no exception, as evidenced by the abundant and awkward whispers during the orchestral interludes, as if they didn't matter. However, there was little applause until Don José's aria, with Micaela's aria in the third act receiving the strongest one. However, the audience was more generous with at the end, giving a standing ovation to Akhmetshina and González. Carmen continues to charm audiences; the performance passes so quickly that, regardless of whether it was well or poorly performed, when it ends, one immediately wants to see another show. Let's hope it's not another eight years before it returns here.

Any reproduction of my text requires my permission.