Me pregunto si con esto he cubierto mi cuota de teatro hablado y musical de este año, que es una anécdota, al lado de mi programación de ópera, zarzuela y sinfónica. Hace año y medio caí trampa de mi propio morbo y fui a ver esa vacuidad llamada Malinche, en el que Nacho Cano se autocomplacía con un bodrio de lujo. Muchos allegados a mí me recomendaron ver The Book of Mormon, un exitoso musical procedente de Broadway, donde lleva catorce años en cartel. Anunciado en metro, Youtube y redes sociales, se estrenó hace un par de años en el augusto Teatro Calderón -que fue teatro de ópera durante la época de la Segunda República y los primeros años del franquismo- , pero desde esta temporada está en el Teatro Rialto de nuestra Gran Vía, el pequeño Broadway español. Finalmente me animé ayer.

Voy a hablar desde mi ausencia de conocimientos del mundo del teatro musical y de la religión mormona. Pero si hablaré de las impresiones que me ha generado, y de por qué me parece una obra tan hilarante como brillante.

Cuando uno ve los anuncios de este musical, con esos actores tan pulcros y sonrientes, especialmente el que encarna al Elder Price, el protagonista, tan rubio, blanco, de ojos azules y de sonrisa Profident como los mormones que se ven por ahí, intentándote hablar sobre Dios (conmigo lo intentó uno en el metro, tratando de conquistarme con su amor por la comida peruana y el cebiche, pero no recuerdo más porque duró poco la charla), o los testigos de Jehová que tocan cada puerta. Uno sabe que se va a reír, pero si no averigua un poco más, se puede encontrar con toda una sorpresa una vez se siente en su butaca. Empezando porque los creadores de esta obra son ni más ni menos que Trey Parker, Robert Lopez y Matt Stone. El primero y el tercero son también los creadores de South Park, esa legendaria serie de dibujos para adultos tan horribles como irresistiblemente soeces y satíricos.

Estados Unidos es una sociedad de contrastes: hay una parte culta, muy diversa, liberal, con aportaciones de todas las culturas que lo han formado, muy desarrollada tecnológica y artísticamente, en la que me gustaría incluírme si viviera allí porque la admiro muchísimo, pero también hay otra parte conservadora, retrógrada, que cree a pies juntillas que la creación del mundo es como en la Biblia, profundamente inculta y racista, consciente o insconscientemente tendente al supremacismo de la "raza" blanca, que además tiene el suficiente poder para limitar a la parte más cultivada. Y este musical, creado en el liberal y ultramoderno Broadway neoyorquino, viene a satirizar el peor de los lados de esa sociedad tan contrastada, que es la que cultural, económica, y ahora parece que también militarmente, manda sobre nosotros.

Los mormones tienen una importante presencia en ese país, con Salt Lake City como su capital, con su neogótico y gigantesco templo. Desde ahí, se dirigen a todo el mundo para llevar la palabra de Dios... y de Joseph Smith, fundador de la orden. Y es en este punto cuando encontramos a nuestro protagonista, el carismático Elder Price, quien sueña con ir de misión a Orlando, Disneylandia, pero al que destinan a Uganda, y para su desgracia, junto a él va un hermano tímido, poco agraciado, basto, con sobrepeso y con muy baja autoestima, el Elder Cunningham. Ambos hermanos no solo no saben nada del país ni de su gente, sino que durante toda la obra no hacen más que confundir el nombre con Uruguay o Yugoslavia. El mundo africano que se encuentran es un sitio colorido, pero miserable. Allí se encuentran con unos hermanos que no solo no han conseguido convertir a nadie, sino que viven víctimas de sus propias represiones y fantasmas. A los ugandeses no les interesa la palabra de Dios, ya tienen bastante con sus problemas: el VIH extendido, la represión de un general local, la ablación de clítoris, la pobreza...

Esto podría dar para un drama, pero el libreto lo pasa por el filtro de la comedia brutal y tronchante. Porque la pluma del Elder McKinley, quien de acuerdo a las enseñanzas mormonas, trata de reprimir a duras penas su homosexualidad (porque a los homosexuales el libro mormón les prescribe la castidad), la forma en que los africanos son representados como personas miserables, ignorantes (como que uno de ellos crea que por tener sexo con un bebé se le cura el sida, toda una alusión a los abusos a niños en las iglesias estadounidenses), enfermas y reprimidas; la incultura total de los hermanos que creen que Uganda es como en la película El Rey León, la soberbia del modélico Elder Price que demuestra ser un cobarde, dejando solo al Elder Cunningham con la misión... son una verdadera patada en la entrepierna a la pacatez conservadora y racista de la sociedad blanca estadounidense. Ahí reside la brillantez de esta obra, porque nada es lo que parece. El verdadero protagonista no es el rubio atlético y carismático Elder Price que huye a la primera de cambio, sino el bajito, gordo y moreno Elder Cunningham... el que consigue la conversión de toda la aldea, incluso si para ello tiene que engañarlos metiendo anécdotas de su invención. Y pese al ridículo, el horror del presidente mormón cuando descubre el engaño, dejando entrever su racismo y clasismo... los hermanos consiguen una conversión sincera de los aldeanos, que una vez unidos en la esperanza de la Palabra (aun en una versión llena de invenciones), se libran del yugo del general, y serán los nuevos mormones de África.

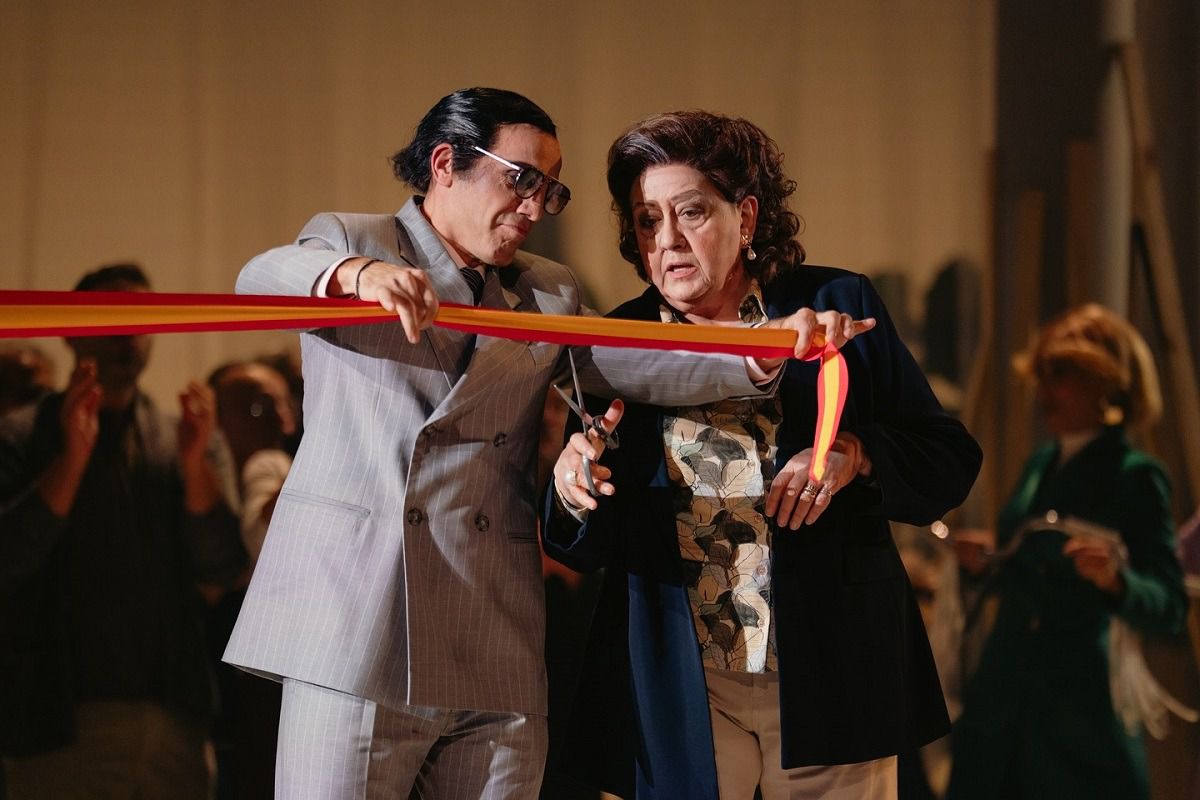

Todo esto es llevado a la escena del Rialto en la producción de David Serrano (quien junto a Alejandro Serrano se encarga de la traducción al español, todo un reto a la hora de introducir una historia tan americana en sus temas, como en las onomatopeyas como la muy americana "Oh, Guau" que dice el Elder Cunningham), quien consigue crear ese mundo de ensueño y colorido, que transmite una realidad descarnada en tono de comedia casi zafia. Nada más entrar en el Teatro, las palabras "THE BOOK OF MORMON" reciben al espectador. Aunque la recreación cómica de la historia del Libro de Mormón y la impecable sala del centro de formación son bellas a la vista, lo importante son las escenas africanas, obra de Ricardo Sánchez-Cuerda. Y estas aparecen con unos colores vivos, aunque no dejen de recordarnos la pobreza, presididas por un destartalado coche arriba del todo.. Las escenas de explicaciones y de sueños también son un universo aparte: cuando Elder Price sueña con Orlando, primero quemándose y viéndose él mismo en el infierno, con Hitler, Gengis Kan, el asesino en serie Jeffrey Dahmer y con Silvio Berlusconi (en la versión en inglés es el abogado de OJ Simspon, el boxeador)... es una joya absoluta. A Iker Karrera se le debe la estupenda coreografía y a Joan-Miquel Pérez la dirección musical de las animadas canciones.

Poco que decir sobre el excelente elenco, aunque los dos hermanos no son los mismos que lo estrenaron en Madrid allá por octubre del 2023. Alexandre Ars hace creíble al Elder Price, que de guapo, siempre sonriente, carismático y virtuoso resulta repelente. Y como el verdadero protagonista, Jesús González (quien se alterna en el rol con el principal Alejandro Mesa) transmite un Elder Cunningham gracioso, que baila muy bien y que trasmite su inseguridad al público, como el compañero que a priori nada querríamos tener, poniendo a prueba nuestra superficialidad. Me arriesgo a decir que la mejor voz del elenco es la de la catalana Aisha Fay como la crédula e inteligente Nabulungi (a la que Cunningham pone muchos nombres como Jumanji o Enantium, una prueba más de involuntaria soberbia al no esforzarse siquiera de pronunciar su nombre), con su potente canto, y el tierno retrato que hace de su personaje. Los mejores números fueron los cantados por ella. Del resto de personajes, muy divertido Alberto Bolea como el reprimido Elder McKinley, Álvaro Siankope como el aldeano que tiene chinches en la entrepierna (sí, así de soez es el libreto), y gracioso y brutal al mismo tiempo Ricardo Nkosi como el General Puto Culo Desnudo, de imponente porte y presencia en escena, quien también interpreta al Diablo en la canción de pesadilla del Elder Price.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.