In 1975, the filmmaker Hans Jürgen Syberberg interviewed a key figure in the history of the Bayreuth Festival, Wagnerian history and the cultural life of the Third Reich: Winifred Wagner , the maestro's daughter-in-law. Between 1931 and 1944, Winifred managed the Bayreuth Festival, during its most troubled period of history: when it became the main cultural temple of Nazi Germany, due to Adolf Hitler's admiration for Wagnerian work and his closeness to the composer's family, especially to Winifred. The artistic achievements that took place at that time are undeniable: working with director Heinz Tietjen and scenographer Emil Preetorius, the Festival reached its greatest glory at that time. Tietjen modernised the Festival's staging, not without controversy due to Wagnerian orthodoxy, replacing painted curtains with the best stage technology of the time. Although the ultra-conservative, anti-Semitic and xenophobic Bayreuth circle and later the Nazi government kept many of the best Wagnerian artists of their time away because they were Jewish, left-wing or "modern", great voices such as Max Lorenz, Frida Leider, Marta Fuchs, Rudolf Bockelmann or Germaine Lubin, or great conductors such as Artturo Toscanini (only in 1930 and 1931), Wilhelm Furtwängler, Karl Elmendorff, Richard Strauss or Hermann Abendroth could be heard at the Festspielhaus. However, beyond music circles, this period has gone down in history for many because of the close friendship between Winifred Wagner and Adolf Hitler.

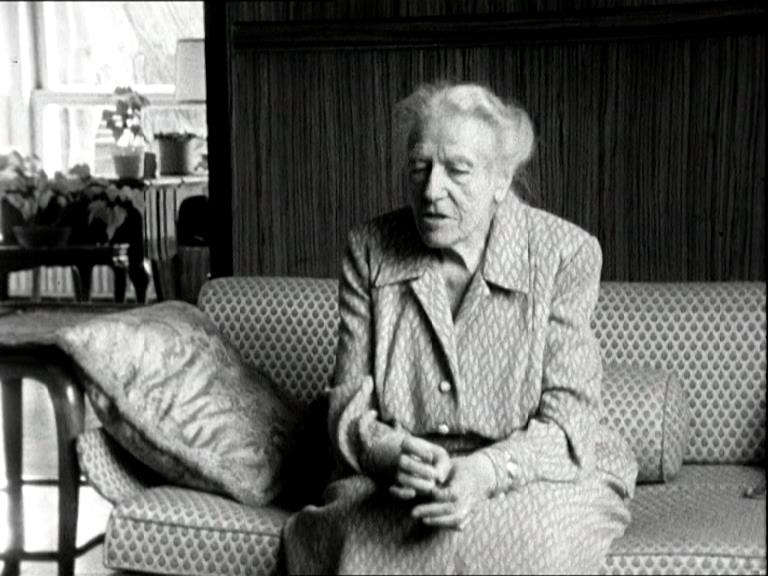

During five hours, Syberberg gives voice to Winifred Wagner, a controversial figure, so that she can tell not only the story of her life, but also express her thoughts, including her experiences during the Nazi era, in that time (1975) when no one who had lived through it dared to speak too much about it in public. It seems as if all the material was displayed, without editing or removing anything, with the only interruptions being the change of reels. A black and white cinematography that could seem rudimentary for the time, especially when photographs appear, but which ends up becoming a window into the soul of this woman and of old Bayreuth. The film begins with Wagner's Siegfried Idyll in the background, a piece composed for the birth of Siegfried Wagner, son of the maestro and husband of our protagonist, while photographs appear of a Wahnfried that in 1975 had not yet been rebuilt after the war and was still in ruins.

I must admit that after having seen it, I am not sure how far I should judge Winifred as I used to do until then, but, I must give her credit for her not always comfortable frankness.

Winifred Wagner was a self-made woman. And that is something she conveys from her story of her difficult childhood, of how she was orphaned so early, and how she was stumbling around, in an orphanage and with German relatives, until she met Karl Klindworth, who knew Wagner, and who introduced her to the world of Bayreuth and the maestro's family. Thus she entered into the mysterious and peculiar family of the maestro, who despite having died thirty years earlier, continued to influence their lives. Winifred tells us about her early years, the routines of Cosima Wagner and her daughters, in a description from a manual of customs of the time, how the First World War affected the family, which among other things led her to grow potatoes in Wahnfried, to the scandal of many. She also reveals that she had to assist her husband in his work, which kept her away from raising her children. After the Festival reopened in 1924, the atmosphere among the public became increasingly xenophobic and ultra-nationalist. One example is that on one occasion when Winifred had to speak in English, someone reproached her for it, because only German should be spoken at the Festspielhaus. Her closeness to the management of the Festival made her ideally suited to replace her husband after his death in 1930, despite the scepticism of many.

However, the most substantial part is what comes next. Unlike another culturally relevant woman of Nazism, Leni Riefenstahl, who always looked for excuses and knew how to hide what didn't suit her, even lying if necessary, about that period, Winifred Wagner is as sincere as she can. Even in her admiration for Hitler, neither the politician, nor the genocidal, but the man with whom she maintained a beautiful friendship, and who supported the festival with almost unlimited means. During the documentary, Winifred tells things that make us think to what extent that friendship deepened, although she denies any romantic attraction. She was one of the few people who was on first-name terms with the dictator and whom he was on first-name terms with. She tells us of an affectionate relationship, of a Hitler who was truly happy both in the theatre and with Wahnfried, who found in Winifred and his children the family (who called him Wolf) that he would have liked to have. Winifred tells us about the dictator's insane festival routines, waking up at noon and going to bed at dawn. She also tells us about their arguments over each performance. Bayreuth maintained its independence from the clutches of Goebbels and Göring, who controlled the German theatres, but somehow it seemed to please Hitler, if we take into account the arguments they had, at the end of each performance, over the artists and the programming of each festival. She even tells us a curious anecdote: the dictator thought that the wicked Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, a hunting enthusiast, would give up his hobby after seeing the scene in which Parsifal is captured by the Grail Order after hunting the swan. Rosenberg was not a big fan of Wagner.

But it is from here that the controversy begins, although it must be acknowledged that she used her power to save some Jews and other persecuted people like Max Lorenz, a homosexual married to a Jewish woman; among other cases that would speak in her favor in her denazification process. Winifred Wagner may have been more sincere than Leni Riefenstahl, as has been said before, but like the filmmaker, she only looked out for her interests and did not care about anything else. A very human attitude, even more so taking into account that confronting the Nazis was a suicidal idea, and that the "Aryans" were so well treated that they did not have to worry about the oppressed minorities. Winifred only recognizes that the second half of the war from 1943 was condemnable. It seems that she didn't noticed the 1933 boycott of Jewish businesses by the demonic Sturmabteilung troops, the 1938 Kristallnacht, even though it also affected Bayreuth: synagogues were attacked and the main 17th-century synagogue was saved from burning because it was close to the Margrave's theatre. Not even the ban on "non-Aryan" music; in fact, she says that she did not care that Mahler's music was banned, because she did not like it. However, her enthusiasm for the Hitler she met in Wahnfried, even after the war, is where her fault lies. Although not everyone had the courage to flee as her daughter Friedelind did, she could well have recognised all the crimes of the regime and distanced herself from it as Wieland did, even though he benefited from it. But, in another human reaction, that of clinging to something or someone that is very dear even if it is something or someone horrible. The fear of losing that reference. Winifred fears losing her attachment to everything beautiful that she knew, even if it was horrible and criminal for other people. Indeed, she mentions that she refers to Hitler in code as "USA" (Unser Selige Adolf, in German "our blessed Adolf"). The documentary doesn't mention it, but it is said that she used to sign some of her letters with an 88 (which means Heil Hitler), or that she was sceptical about the final destination of the famous contralto Ottilie Metzger: Auschwitz, apart from inviting to the Festspielhaus such people linked to Nazism like Hermann Göring's daughter Edda. That is where her guilt lies, even if she only speaks freely about something that many Germans of her generation kept quiet about. Winifred Wagner believed in National Socialism, and although she seems to recognise its errors, she doesn't care too much about them, she remains clinging to it. Even she blames the infamous tabloid owner Julius Streicher, not Hitler, for the antisemitic waves during those years! Streicher was disgusting even to the regime enthusiasts like her. At least, all this shows that this woman's unconditional friendship was a privilege of incalculable value.

This documentary is a valuable testimony to the history of the Bayreuth Festival and Germany, both of which are so closely linked. But like the 1993 documentary on the life of Leni Riefenstahl, it is also a testimony to the human condition, to how to look out only for one's own convenience and to ignore the injustices on other disgraced people. Even more so when this happens in a regime that viciously prosecutes any kind of dissent. A typical attitude in Nazi Germany, but still current in 2024, in our placid and democratic West, while we watch injustices and wars live in our smartphones and televisions.

Essential for any Wagnerian, and for every history enthusiast.

My reviews are not professional and express only my opinions. As a non English native speaker I apologise for any mistake.

Most of the photographs are from the internet and belong to its authors. My use of them is only cultural. If someone is uncomfortable with their use, just notify it to me.

Any reproduction of my text requires my permission.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario