There are not many chances today to see some of Hans Pfitzner's music in opera houses and concert halls. In fact, if it happens, they are usually limited to an orchestra playing the three preludes to his opera "Palestrina", his best-known work. And if this opera is performed, it is usually done in Germany, Austria or Switzerland. But even in this case, this is not very frequent. Maybe, because of two main reasons:

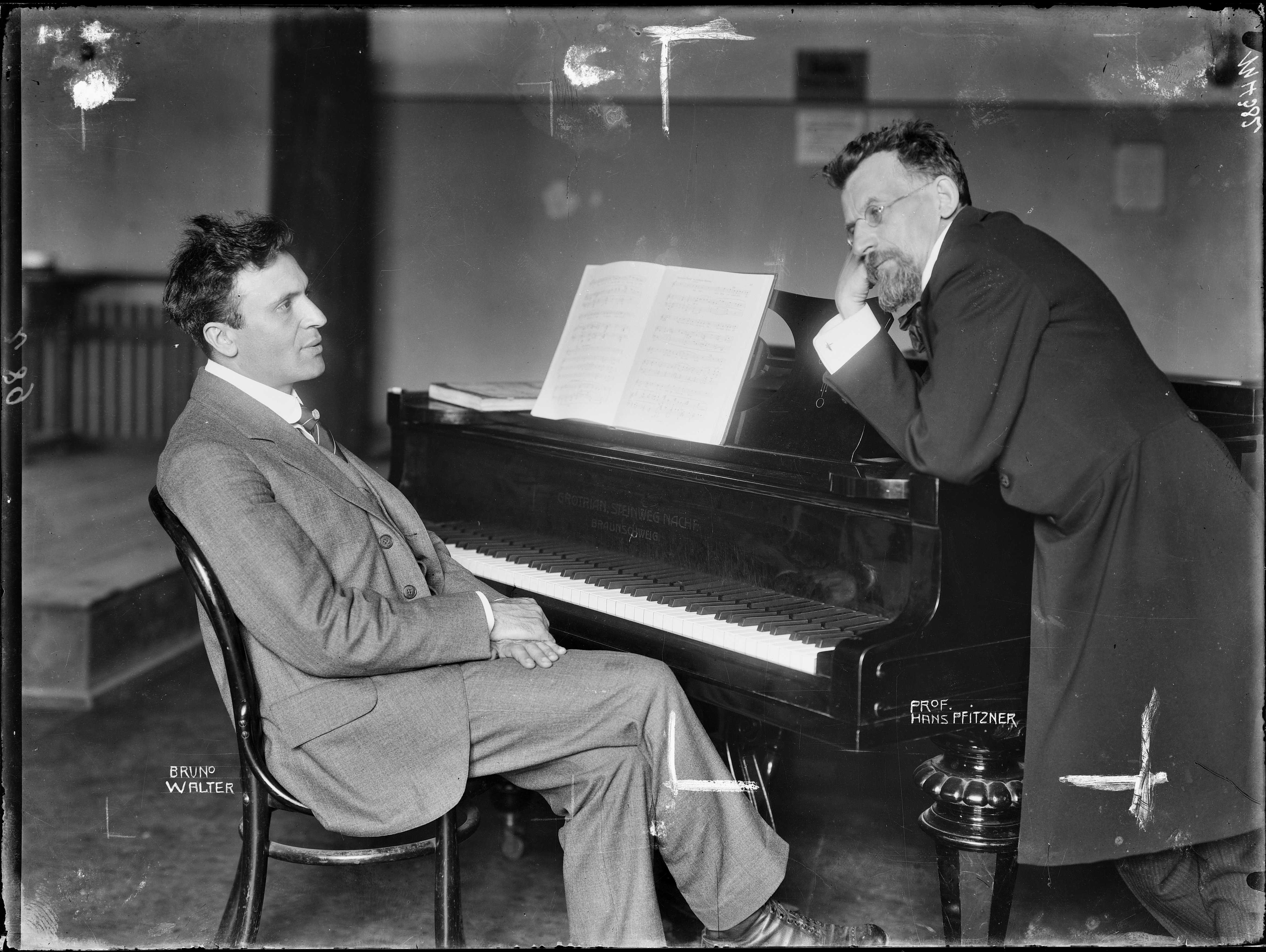

The first and well-known one is that Pfitzner sympathized with the Nazis. From his youth, the bad-tempered Pfitzner was openly anti-semitic. He even had the indelicacy to tell a Jewish friend that he had been trained as an anti-semite during his youth in Berlin. This did not prevent him from having Jewish friends and supporters like Bruno Walter, who premiered this opera in 1917. Another jew, Selmar Meyrowitz, premiered the beautiful (now forgotten) cantata Von Deutscher Seele (From the German Soul, based on poems by Eichendorff), in 1922. Pfitzner believed that some "noble" Jews were enough patriotic to be honorable Germans. This is something that would cause him some problems later. In the early 1920s, Adolf Hitler visited him in the hospital, and after discussing this issue with him, the future dictator was so disappointed that he didn't want to have anything to do with him, even he believed that Pfitzner was half-Jew, which for him was unacceptable. Indeed, Pfitzner had to prove his Gentile ancestry. Although during the Nazi period he was one of the most favored and scheduled musicians in operatic and symphonic venues, Pfitzner did not obtain the recognition in life that he expected. He was forced to retire and his pension was not very high. In fact, he had to resort to seeking the friendship of senior Nazi officials in order to thrive. Notorios was his friendship to the infamous Hans Frank, General Governor of the Nazi-occupied Poland, and responsible for the deaths of millions of people. During the war, he conducted in occupied countries such as Poland and France, where he attended a Palestrina performance in 1942.

Despite that he didn't agree with the nazis completely, even he rejected to put music to Shakespeare's A Midsummer night's dream because Mendelssohn's music was banned, the end of the war did not bring about a change for him. He went so far as to write that "World Jewry is a problem and, in fact, a racial problem, (...), and it will be taken up again, so people will remember Hitler and he will be seen differently that he is now (...) it was his innate proletarianism that led him to assume the position of an exterminator called to destroy a certain type of insect, in the face of the most difficult of all human problems. So he should not be blamed for the "for what", nor by "that he did it", but only by "how" he approached the task (...) World history has already seen that a human race can be exterminated from the surface of the earth, with the extermination of the originally magnificent Indian race […]. In terms of international morality and customs of war, Hitler could really feel "covered" by this single example; the "how" of these acts of violence and methods of oppression is, of course, condemnable itself, as long as it is based on truth and not is deliberately exaggerated. It is possible that terrible things have happened in the concentration camps, as they always happen in these periods of unrest, as isolated cases and by subaltern brutes, as they always and everywhere happen, but even less so among the German people. But if we, the Germans, wanted to make a contrary calculation of the atrocities that were committed against us [...], the relationship between guilt and accusation of crime and judicial function would enormously change and be reversed."

Was Pfitzner trying to imply since the Native "Indians" in the Americas disappeared, then Jews could do it too? Any disappearance of an ethnic group is a tragedy for humanity, not a "single" example. Although he was acquitted in his denazification process, Pfitzner's reputation remained irremediably stained to this day, this categorization as a "Nazi" musician being the main obstacle to his greater and deserved presence in concert halls. Pfitzner, having lost his family during the war, died in 1949 in Salzburg, aged 80.

The second and no less important reason is that Pfitzner openly declared himself an openly anti-modernist, living in a time when symphonic and vocal music was experiencing a period of constant effervescence and experimentation. In fact, he used to consider himself a custodian of German musical tradition. As a result, his fame was specially limited to the German-speaking world. His music (and this is something that would also happen with less renowned composers favored during Nazism) is very beautiful, it adds, but it does not contribute anything new, despite its complex, rich musical language. For example, Von Deutscher Seele is a beautiful cantata, with many inspired moments, but its impact couldn't reach those ones from masterpieces such Schoenberg's Gurrelieder or Mahler's Second Symphony. Another Pfitzner's amazing works are the violin concerto op. 34, the cello concerto op. 42, the symphony op. 46"An der Freude", the orchestral lieder, the overtures from operas such as Der Arme Heinrich or Das Christelelflein, or the musical suite for the theatrical play Das Kätchen von Heilbronn, are some of his works that do deserve to be in concert halls more frequently, although most of them did not have the same musical impact as the symphonic poems of Richard Strauss, or the music of Britten, Stavinsky or Shostakovich. Even when his work has been more performed and recorded (Werner Andreas Albert's recordings for the CPO label are an example) from the 80s and 90s, it mostly seems to happen mainly in Germany and Austria.

Palestrina was premiered in 1917, with enormous success, and remained in the German repertoire even until few decades after World War II. Considered a "musical legend", Pfitzner compares himself to Palestrina: the Holy See debates, among other issues, banning polyphony, a symbol of secularization, and which had been an innovation in sacred music, to return to " purity" of Gregorian chant. Palestrina defends his art, from the elite, from selling himself to the power that, represented in Cardinal Borromeo, coerces him to compose a mass that allows him to save polyphony. He prefers inspiration, and rather than being forced to compose. Pfitzner aims to defend his conservative art from the "dangers" of the modernization of music, so accepted by the cultural elite. And like Palestrina after losing his wife, something that influences his loss of inspiration, Pfitzner became an embittered social hermit due to the tragedies of his life, although this would happen after 1917. The second act takes place at the Council of Trent, where no one agrees on anything, and in the end the great conflict that ends in a fight is repressed with executions and torture: a prophetic allegory of what will take place in Germany during Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. There is a lot of influence from Wagner's work, the first act is musically indebted to Parsifal, especially in the first overture, where the main motif of the work is heard. The first act is undoubtedly the most beautiful. Afterwards, there are moments of great beauty and musical color, alternating with others of the same kind. Still, the orchestration, as several have pointed out, is quite interesting. The second act, with so much discussion, may remind us of Tannhäuser or the Meistersinger, but as Pfitzner rightly said, without reason for laughter. The third act is beautiful musically, but without the inspiration of the first. The work ends with a brief reflection by the musician before he begins to play the organ, closing the work with the main motif of the overture.

Such a problematic composer's musical legacy needs an initiative to have it performed today. And Palestrina's main supporter in present day's Europe is the German maestro Christian Thielemann, with a reputation for being conservative beyond the music. Almost 30 years ago, he conducted this opera in London and Vienna. Now, 23 years after its last performances in the Austrian capital, this title returns to the Vienna Opera conducted by Thielemann, in the same production by Herbert Wernicke, which was seen decades ago on that same stage. Now, for posterity, the December 12 performance is immortalized in streaming. Until now, there used to be only one video of this opera, coming from Munich in 2009, but if this recording becomes a DVD, it will become the referential video and the most important recording of this opera in 21st Century.

Wernicke's staging sets the opera in what it seems a white musical auditorium, with a big pipe organ presiding the stage, and orchestral instruments with music stands and scores. In the middle, there is a table in which Palestrina composes his works, and at the left there is a small church organ. The staging sets the action in a contemporary era, and Palestrina appears as a visible Pfitzner's alter-ego, and characters dressing in modern suits. During the big Act One finale, Palestrina will take seat and compose the famous "Pope Marcello Mass", and the aparitions are actually choristers. His wife Lucrezia will appear in a red dress, as a famous operatic diva. The organ opens to reveal a big choir, the angels dictating Palestrina the music. Act Two opens in the same hall, but instead of the pipe organ, stalls are seen, in which aristocracy will attend the Council. The chorus is divided between cardinals and the Spanish and Italian parties, dressed in police, military customs. At the finale, there is a big quarrel, to which army stops by shooting the fighting people. In Act 3, we see again the instruments and the big pipe organ. As a remarkable moment, Pope Pius IV appears in the Royal Box, like a divinity to which Palestrina, Ighino and the chorus on stage kneel before. The opera ends with Ighino playing the organ and a tired, frail Palestrina taking the score and starting to conduct as the curtain falls.

Thielemann's knowledge of this opera is noticeable by his amazing conducting, one of the best I have seen from him in any recording. His conducting style, so slow, so majestic, so Germanic, here makes every instrument to shine and to sound lyric, as this is an opera about a personal conflict. Thielemann conveys his command of Pfitzner's music to the Vienna Opera Orchestra, whose instruments sound inspired, beautiful, as his style of conducting fits on what Pfitzner wanted to convey in his music. The famous Act One prelude sounds slow, elegiac, mystical, Act Two prelude is passionate, spectacular, and Act Three prelude sounds as the serious and calm sister of Meistersinger's Prelude to Act 3. Strings (specially cellos during Palestrina's inspiration in Act 1), flutes, the brass in Act Two, all sound amazing. The Chorus sings very well too.

Apart from its big orchestra and chorus, this opera requires from a big cast: a leading tenor, followed by difficult roles for basses and baritones.

Michael Spyres sings the title role: this tenor who is doing Wagner roles in recent years, has a baritonal voice (as he used to be a bel canto baritenore for Rossini and Bellini operas) which portrays a depressed, tired Palestrina, in despair for not being inspired and grieving his dead wife. His acting conveys an early aging man who wants his freedom to create. The females are accomplished singers: Kathrin Zukowski is a sweet Ighino, as well as Patricia Nolz as a well sung Silla. Wolfgang Koch is the strong-tempered Cardinal Borromeo, with a matured voice, not always deep in sound, but still showing good singing. Spieltenor Michael Laurenz is a big-voiced Cardinal Novagerio, sounding here as a Mime-like scheming and grotesque character, as well as Hiroshi Amako as the Abisinia Bishop. Michael Kraus has also sung well the role of the Lothringen Cardinal. Günther Groissböck sings beautifully and his imposing presence is suitable for the role of Pope Pius IV, in one of the most magic moments of the performance.

As this is a rarely performed opera, this performance has been quite a big event in German-speaking musical world. Such enthusiasm is perceived in the outstanding ovations at the end of each act.

Pfitzner's work deserves to be more performed by world-class orchestras, and Palestrina is an opera that should be seen more often, in all major opera houses, because of its beauty. But for its current limited programming, apart from the obvious big resources needed, maybe an important reason lies: Hans Pfitzner himself.

Because what this embittered man sowed with his decisiones and some attitudes in his lifetime, his works reaped today through unfair neglection. So sad.

Here, you can make your own opinion of this opera.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario