Since 1951, scandal has not ceased to appear at the Bayreuth Festival. First with Wieland Wagner's productions, which in their time shattered the Wagnerian tradition, although in 2024 they would be considered ultra-conservative, it wasn't until 1972 when Bayreuth did have its first contact with the Regietheater. It had been only six years since Wieland had died, and the high artistic levels fixed by his productions were in decline. Accepting his own inability to maintain them by relying only on his artistic ability, Wolfgang Wagner hired Götz Friedrich, a young East German stage director, to direct Tannhäuser. Until then, Wieland's stagings for this opera had already upset the audience with their choreographies that were described as obscene and gloomy, and in 1961 he had scandalized Wagnerian orthodoxy with Grace Bumbry's Black Venus. But they had no idea what was coming to them in 1972.

Friedrich was a student of Walter Felsenstein, who in the GDR was revolutionizing the scene with a movement called "regietheater", focused more on drama and performance than on being at the service of music. As Frederic Spotts would quote in his Bayreuth History book, that year the public became the aristocracy of Wartburg and Friedrich became Tannhäuser. In 1978, in its last year, this production would make history again, this time to be the first from Bayreuth to be completely filmed.

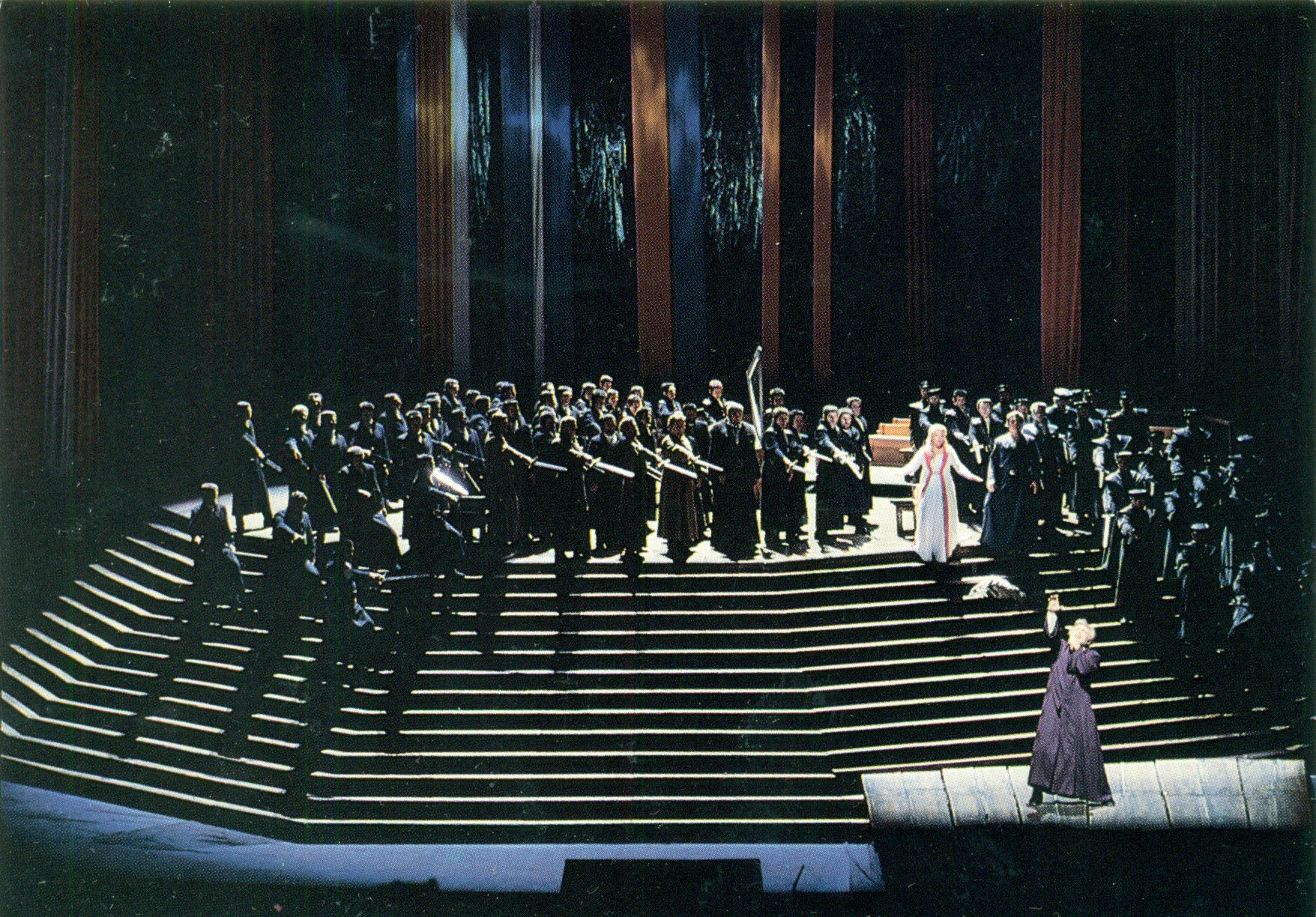

Tannhäuser is an alter ego of Wagner, an outsider, a rebel who is not understood by the refined and religious society of his time, and with fickle thoughts, divided between the pure love of Elisabeth and the frenetic passion of Venus, clearly in love with him. A free artist who can't find his place in the world. Friedrich echoes all this, applying the regietheater methods. The overture is staged: on a stage platform, surrounded by black curtains, with a small triangular hole in the centre, on which the staging develops, Tannhäuser appears alone, with his lyre, thoughtful, anxious, before the furious bacchanal, choreographed by the mythical John Neumeier, much more radical and sexual than Wieland's. Long red threads appear on the stage, with the bacchantes giving free rein to frenetic dances, with nods to fetishism and sadomasochistic domination, with some dancers dressed in leather and wearing masks. At the end of the dance, three skeletons appear, the final icing on the cake of an orgy of perversions, death and destruction. Venus appears masked, with a dress made only of tights that reveals her nudity (this is really a costume), a sensual, sadistic and frivolous goddess, with an air of Joan Crawford. The second scene (and also the set of the third act) is the entire deserted platform, with the statue of the virgin on one side. Pilgrims who go to Rome carry a wooden cross on their backs. The singing knights of the Wartburg appear in processions, with suspicious leather uniforms reminiscent of certain vermin that ruled Germany just a few decades ago. The second act shows the Wartburg hall elevated by many steps, giving an idea of the exclusive and elitist world that Tannhäuser left for the Venusberg. During the entrance of the guests, the banners are raised. The costumes of the ladies, pages and ushers are medieval, but that of the male guests is totally black, with badges and insignia, and leather jackets that are blatantly reminiscent of the Nazi SS, and even after the famous chorus they a somewhat fascist salute. A harp that must be touched to take turns, although Wolfram, Tannhäuser, Biterolf and Walther prevent poor Heinrich Schreiber and Reinmar from taking theirs , despite their efforts g. When he falls from grace after singing his anthem to Venus, Tannhäuser descends the steps, a sign of the fall from grace of those who break the rules, something that could be applied today to cancel culture. The third act is the same platform as the first act, all deserted. In the prelude to it, an aged, suffering Elisabeth is seen crying for her beloved. Wolfram watches her, accompanied by the shepherd boy. The old pilgrims arrive and Elisabeth cannot find them. After her prayer, she crawls alone across the stage, offering that sacrifice to God. In the end, Tannhäuser is dying while the choir of young pilgrims, with the stage darkened, as if they were actually angels, sing offstage announcing the miracle of his redemption. After exhaling its last breath, the entire choir sings its last lines, with the stage illuminated, closing the work in a final apotheosis.

Friedrich removes, as Wieland already did, any unnecessary props from the stage to concentrate on the drama, reducing the performance to the most absolute essence of the work. He succeeds, not only because of the controversial staging, but also because of the impressive acting direction, achieved by competent singers and the excellent camera: thus we capture the eager and then almost orgasmic expressions of Tannhäuser in the first act, the frivolity of Venus, the unconditional, sweet but at the same time energetic Elisabeth in the second act, and then totally destroyed in the third, the passion and chemistry with Tannhäuser, when he sings his hymn to Venus, how he falls into her chair in ecstasy, and then her sorrowful expression during the rest of the act, how they try to touch each other, separated by the steps, before he leaves for Rome and bids her farewell with a tragic gesture.

Colin Davis conducts the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra in a remarkable way, agile, with dramatic tension, rather fast tempi, which accompany the tragedy more than recreating in the majesty of the music. The Festival Choir, as always, at a high level.

Spas Wenkoff sings Tannhäuser. One wonders why this Bulgarian tenor did not have greater stardom than he deserved and more presence in the recordings of Wagnerian operas, since he is at the same level at contemporary colleagues such as Kollo, Domingo, Jerusalem or Hofmann. Wenkoff is a tenor with a baritone-toned voice, heroic tone, firm projection, powerful volume, and doesn't arrive tired to the great Act 3 narration. He is also an excellent actor, since his expressions (in the second act he conveys Tannhäuser's feeling that none of his rivals are at his level) and movements convey the tragedy of the character.

Gwyneth Jones overcomes the challenge of singing Elisabeth and Venus in the same performance, something that few sopranos do on stage, and in a more comfortable tessitura than Boulez-Chéreau's Brunnhilde of the Ring that she sang around the same time in Bayreuth. Here, in fact, the voice is beautiful, firm, high notes not so shouted, and there are flashes of lyricism, which suggests that Jones perhaps should have stuck to sing the "light" Wagnerian heroines. And as an actress she is convincing, in fact her best moment is Elisabeth's final prayer, both singing and acting.

Bernd Weikl is an excellent Wolfram, perhaps he lacks a little low voice, but his singing is refined and elegant. Hans Sotin is also a more than competent Landgrave, although the vocal surprises come from both the legendary Franz Mazura in his brief intervention as Biterolf, excellent, and from Robert Schunk as a more romantic, heroic Walther than the usual spieltenor singing The boy Klaus Brettschneider, from the Tolzer Knabenchor, plays the Shepherd Boy, something that rarely happens in this opera.

This controversial production meant the first contact, for the Bayreuth conservative audiences, with regietheater, and paved the way for its definitive setting with the Chéreau's 1976 Ring. Never before has Tannhäuser been performed so raw, and musically it remains the most interesting of the productions of this opera filmed in Bayreuth, and a classic on DVD alongside the old Met production. A real must.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario