Barcelona, March 19, 2025.

Barcelona is the Spanish capital for Wagnerism. Since the late 19th century, Catalan high culture embraced Wagnerism as one of its musical and cultural landmarks, while Catalonia was living a cultural golden age. Great Wagnerian artists such as Francisco Viñas, Hans Knappertsbusch, Joseph Keilberth, Astrid Varnay, Kirsten Flagstad, Max Lorenz, and Gertrud Grob-Prandl, among many others, have delighted the Barcelona opera-goers with their performances at the Gran Teatre del Liceu. Furthermore, Barcelona is one of the few major cities where the Bayreuth Festival has toured: in 1955, with the historic visit of three Wieland Wagner productions, and legendary singers such as Hans Hotter, Hermann Uhde, Martha Mödl, and Wolfgang Windgassen; and in 2012, when the orchestra, choir, and cast members of that year's festival performed three operas in concert, including Lohengrin, the last time this opera was performed in the Catalan capital. Although the last time it was staged, happened in 2006, in the Peter Konwitschny's controversial staging, which set the action in a school, with the orchestra beautifully conducted by Sebastian Weigle.

The return of this opera to the Liceu, was scheduled for March 2020, but had to be canceled at the last minute due to the COVID-19 pandemic, is a highly anticipated event. The staging has been entrusted to Katharina Wagner, the composer's great-granddaughter and current director of the Bayreuth Festival. Productions directed by her are very rare, so these performances are, for better or worse, a true operatic event.

Katharina Wagner with the robotic black swan.

"Would you trust someone who won't let you ask where is he from, and who tells you not to ask his name?"

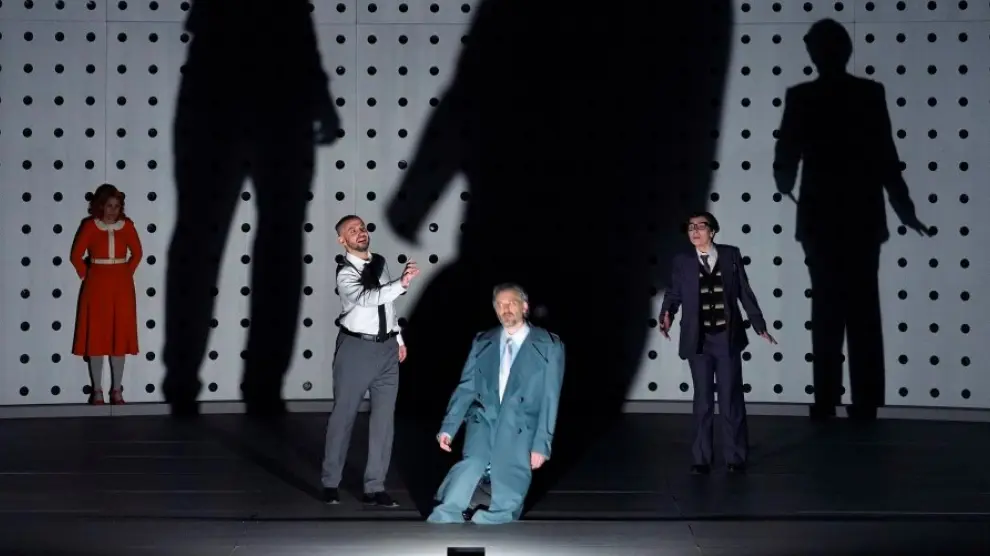

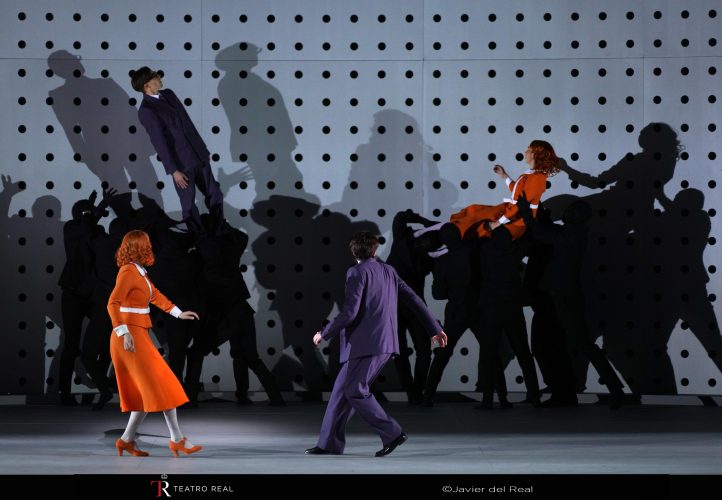

This is what Mrs. Wagner wonders in an interview published last week in the newspaper La Vanguardia. Lohengrin is a Grail Knight who, by divine mission, rescues the helpless Elsa from an unfair accusation: killing her younger brother, Gottfried. In return, she cannot ask him his name. The doubts that the evil Ortrud arouses in her lead her to break the oath on their wedding night, unleashing the final tragedy. For Mrs. Wagner, however, this mystery on true identity is suspicious in the 21st century. So, she poses a 360-degree turn in the story's plot, contradictory to the play's libretto: in this staging, Lohengrin is the villain and Ortrud, the real hero, the one who seeks the truth. Elsa does not seem enthusiastic about joining Lohengrin; in fact, she is forced into marriage by King Heinrich, a clear ally of the hero.

A beautiful, dark forest, created by set designer Marc Löhrer, with a pond in the middle, is present throughout the show. During the prelude, Elsa and Gottfried are seen playing innocently, and then they fall asleep. Lohengrin suddenly appears and convinces Gottfried to play in the pond. He then enters and kills him, drowning him and hiding the body. The entire action has been witnessed by a black swan. This black swan moves its wings and head: it is a robot. In the first act, the King, the herald, and the chorus appear, wearing red, military uniforms. Around them, huge boxes are stacked up to execute Elsa by hanging. Elsa is not summoned here; she is awakened, and is unaware of her brother's disappearance until that moment. They are about to execute her when Lohengrin appears, having hidden the black swan in one of the boxes. Ortrud tries to open it without success, as Lohengrin prevents her.

The second act takes place in the same forest: Ortrud and Telramund are dozing, taking the place of Elsa and Gottfried in the first act. From the pond, Ortrud draws a crown and a toy sword that belonged to Gottfried. At Elsa's entrance, three cubicles descend onto the stage, each one is a modern and simple room. Each character sings within each of them, though moving from one to the other. These rooms seem to represent the characters' conflicts and intrigues. At the end of the second act, Ortrud approaches the black swan, which has presided over the scene, while looking defiantly everyone.

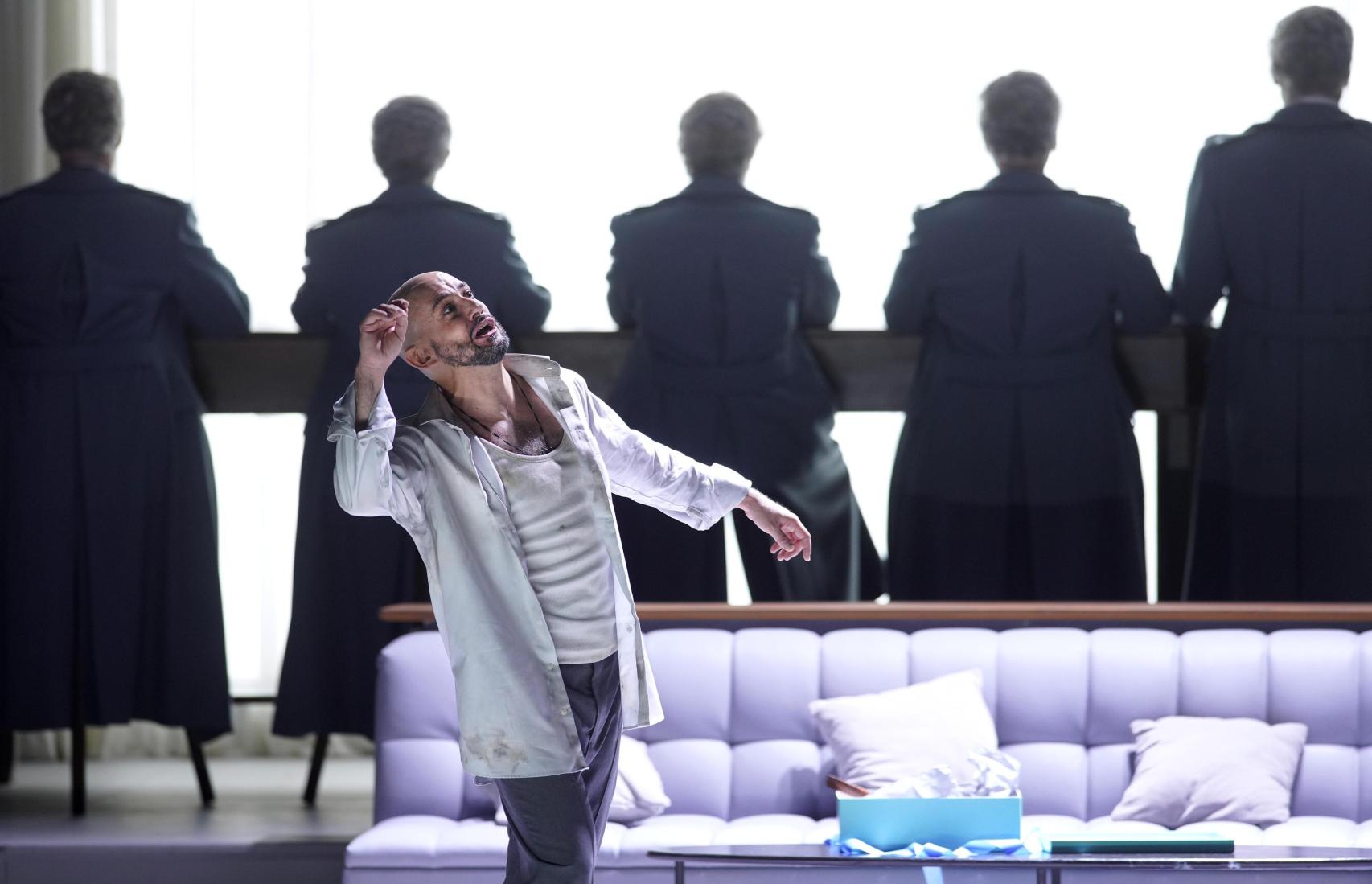

Up to this point, the production bears some resemblance to the original action. But it is in the third act that the production goes too far and loses any connection with the text. The chorus is not seen on stage in the first scene. Lohengrin and Elsa sing their passionate duet in separate rooms, while Ortrud and Telramund wait silently in another one. During the duet, the doors of Lohengrin's cabinet open and the black swan appears, while in the mirror Lohengrin sees the ghost of Gottfried projected. When Telramund enters, he enters with Ortrud, and after a struggle, Lohengrin kills him with a knife, but then Ortrud grabs him and threatens Lohengrin. During the beautiful interlude, the chorus enters the stage and stands in military formation. Lohengrin appears with Ortrud pointing a knife at him. When he reveals his origins, he is left alone, and the chorus and Elsa sing offstage. Thus, his famous aria "In Fernem Land," in which he originally speaks of his sacred lineage, is here a revelation of his sinister nature: several ghosts of Gottfried appear in the background, and two women whom Lohengrin kills but later resurrect. At the end of his farewell aria, Lohengrin commits suicide by cutting his wrists. Then Ortrud pulls Gottfried's corpse from the pond and when Lohengrin says "there is the Duke of Brabant," it is in fact a confession of his crime, after which he dies. While Elsa embraces her brother's corpse, Ortrud and the King stare at each other, and the curtain falls.

Josep Pons , a regular Wagner conductor at the Liceu, has shown his affinity for this repertoire and his enormous effort, taking from the Liceu Symphony Orchestra a spectacular sound, with slow tempos that allow for a sense of delight in the details. Thus, the strings seem in a state of grace, as does the spectacular percussion. The strings sounded wonderful during the prelude, and in the duet scene between Ortrud and Telrramund, together with the woodwind section, they recreated the tense and sinister atmosphere of the conspiracy by these villains. In the prelude to the second act, the beautiful bassoon solo playing the motif of doubt sounded slow and beautiful. The interlude in the third act sounded spectacular. Overall, the level was quite remarkable. The Liceu Choir also gave its all, especially in the second act and at its best, in the brief "Heil König Heinrich" in the third act.

The cast for these performances is top for Wagner operas, they all have performed at the prestigious Bayreuth Festival. In fact, four of the six principal soloists sang in the Tannhäuser I saw last summer there: Lohengrin, Elsa, Telramund, and the King Heinrich.

Klaus Florian Vogt is the most acclaimed Lohengrin today, after twenty years singing the role, albeit with controversial results for several wagnerians. On the one hand, it must be acknowledged that his beautiful and light voice fits well into his entrance in the first act, and throughout the third, when the character has its musically best and most dramatically intense performances. But on the other hand, a more heroic tone is missed in his voice, despite the fact that Vogt sings with all the strength and volume possible, and manages to carry the performance with his stage experience.

But the best one from the cast was Elisabeth Teige 's Elsa : well sung, with a beautiful and seductive, rather dramatic tome, with a well projected voice.

Olafur Sigurdarson was a well-performed Telramund within his possibilities, with a voice that needed deeper low voice, but which strives for a convincing performance.

The role of Ortrud is scheduled for Swedish soprano Iréne Theorin, highly acclaimed in Barcelona. However, she is experiencing many problems. First, an apparently tense relationship with Katharina Wagner due to Theorin's rude gesture toward the Bayreuth audience for booing her, which led to another soprano, Miina Liisa Värelä, to sing at the premiere. But now, a vocal infection has compounded the problem, so for thia performance, she was replaced by Okka von der Damerau. This German mezzo-soprano has a more higher than lower voice. She was still able to pull off the performance, as her Ortrud was very well sung, although she came off rather gracefully in the high notes of the famous, brief curse in the second act. She performed even better in the finale. As an actress, with her imposing stage presence, she recreated an arrogant Ortrud, ready to do anything to stop this evil Lohengrin.

Bass Günther Groissböck played King Heinrich, successfully completing his arduous task. His voice is good, and the low voice is present, but he struggles a bit to achieve the desired projection.

Unfortunately, little good can be said about the Herald played by veteran baritone Roman Trekel. His voice is very worn, wobbling, and his tone sounds unpleasant. At least he impresses on stage, as he is in good physical shape.

The Brabant Noblemen are notable, among whom is the Spanish regular in Bayreuth, tenor Jorge Rodríguez-Norton , and the women who played the young pages.

The expectations raised by this performance run is so high that tickets are mostly sold out for all performances. In fact, yesterday the theatre was almost full. There was great enthusiasm for the cast and the orchestra and chorus, but none for the production. In fact, the stage director, who is no longer in Spain, was highly booed at the premiere. The performance was greeted with thunderous applause and many standing ovations, an example to the city's enthusiasm for Wagner and the Wagnerian spirit of the Liceu audience. To sum up, a great operatic evening.

My reviews are not professional and express only my opinions. As a non English native speaker I apologise for any mistake.

Most of the photographs are from the internet and belong to its authors. My use of them is only cultural. If someone is uncomfortable with their use, just notify it to me.

Any reproduction of my text requires my permission.