lunes, 30 de diciembre de 2024

The tragedy of a queen, a vocal operatic feast: Lisette Oropesa triumphs as Maria Stuarda in Madrid.

Tragedia entre dos reinas, fiesta belcantista: Maria Stuarda en el Teatro Real con un gran primer reparto.

Madrid, 29 de diciembre de 2024.

Una vez más, llega la navidad a la capital, y con ella el iluminado, el gentío haciendo compras para la familia, y el frenesí se apodera de los madrileños durante dos semanas. Este frenesí también llega a la cultura, y mientras el Teatro de la Zarzuela ha realizado una estupenda versión del ballet La Sylphide, el Teatro Real se pone a la tarea con un título lírico que goce del favor del público, y con buenas voces. Este año, el Real cierra la temporada con un título de repertorio, pero no tan clásico como otros años: Maria Stuarda, de Gaetano Donizetti, que forma parte de la famosa "Trilogía Tudor", sobre tres reinas: Ana Bolena reina consorte de Enrique VIII, María Estuardo, reina de Escocia, e Isabel I de Inglaterra, prima de la anterior, cuyas historias se narran en esta ópera, en Anna Bolena y en Roberto Devereux. Tres obras que debe cantar una auténtica primadonna, con tesituras difíciles, y que muchas de las grandes divas han abarcado, aunque no siempre hayan cantado las tres, y de hacerlo, no siempre con el mismo resultado en cada una. No está de más recordar que Sondra Radvanovsky nos dio un memorable concierto con los tres finales de estas óperas el pasado 6 de enero.

Basada en la obra teatral alemana Maria Stuart, de Friedrich Schiller, que ficcionaliza los hechos que rodearon a la ejecución de la desdichada María Estuardo (en italiano, Maria Stuarda), firmada por Isabel I, debido a que se le acusaba de reclamar el trono inglés y conspirar contra su prima. En su obra, Schiller enfrenta a ambas reinas, pese a que ambas no llegaron a conocerse en persona en la realidad. Y el libreto del jurista Giuseppe Bardari recoge esa historia. En su estreno en La Scala, en 1835, no tuvo el éxito deseado y fue prohibida a las seis semanas. Tras casi un siglo de olvido, la ópera regresó al gran repertorio en los años 60 del siglo pasado, con intérpretes como Leyla Gencer, la primera en exhumarla, Beverly Sills, la primera en grabarla, y otras como Montserrat Caballé, Edita Gruberova o Mariella Devia.

Por primera vez en su historia, el Teatro Real escenifica esta ópera en su escenario, aunque Montserrat Caballé cantó esta ópera en la capital en 1979, en el Teatro de la Zarzuela. Y lo hace con dos repartos sensacionales, toda una fiesta vocal que hace las delicias del aficionado a la ópera italiana y belcantista.

La puesta en escena está a cargo de David McVicar, director de escena habitual en el Teatro Real, y que acaba de hacer el Anillo en la Scala. McVicar ya había hecho una versión de esta ópera en el Metropolitan Opera House, pero en esta ocasión es un nuevo montaje. La puesta en escena es de agrado de los espectadores más conservadores Sin embargo, con su oscuridad, trata de transmitir el ambiente de tensión que se cierne sobre la protagonista, a la que la muerte anda rondando, así como el reino de terror en el que Isabel I (en esta obra) de Inglaterra tiene sometida a su corte. l vestuario de Brigitte Reifenstuel es de época, aunque tanto los aristócratas, que visten de negro, como el coro, que viste de colores grisáceos. A lo largo de toda la obra, un enorme orbe dorado, señal del poder, suspendido en el aire, preside imponente la escena. En el primer acto aparece enorme muro dorado en el que aparecen muchos ojos y orejas, y en el centro, una imagen de Isabel I. ¿Una muestra de los rumores de palacio que llegan sobre la situación de María y el complot del que se le acusa? En el segundo acto, caen hojas rojas, lo que podría interpretarse como la sangre de María que pronto se derramará, cayendo como hojas maduras de árbol en otoño. El tercer acto es más oscuro, en la segunda escena aparece un mural de varios puñales rodeando a un caballo, todo ello dibujado en tiza : el cerco se cierra sobre María, ya que ha sido condenada a muerte. En la escena final, no hay decorado: el escenario negro, con todos vestidos de este color y en gris, con María dando la única nota de color, con un vestido rojo, con el que asiste a su ejecución, la cual es un momento tenso, porque al colocarse para la ejecución, agita los brazos de forma convulsiva, mientras cae el telón.

La Orquesta del Teatro Real, dirigida por José Miguel Pérez-Sierra, ha sonado con unos tempi muy rápidos y con los instrumentos sonando muy alto, lo que a algunos les daba la impresión de estar pasado de decibelios. Sin embargo, esto tiene un lado positivo: los tempi rápidos pueden dotar de agilidad y emoción a una partitura belcantista. Además, la orquesta ya tenía rodada la obra, lo que hacía todas sus secciones sonaran bien. Mención especial al violonchelo en varias escenas, y a la cuerda en general en la escena de enfrentamiento de las reinas, así como en la introducción al tercer acto, en el que también destacó la trompa en la introducción orquestal a la gran escena final. El Coro del Teatro Real, dirigido por José Luis Basso, tuvo una intervención memorable, muy especialmente en su gran número de la escena final, en el que las voces volvieron a demostrar su potencial tanto musical como actoral: no solo transmitieron el dolor ante la inminente ejecución de la reina María, sino también demostraron su capacidad vocal: primero empezando las voces masculinas como un susurro, hasta lograr la plenitud en conjunto, en esta sombría pieza, que cerraron con una solemne nota prolongada en la palabra final "rossor", sobrecogiendo al público, que le recompensó con alguien exclamando "¡Bravo, coro!" y luego una ovación.

Para estas funciones, se ha contado con dos repartos excelentes. La función de esta noche ha sido la última del primer reparto, el cual dio lo mejor de sí.

La mundialmente famosa soprano estadounidense Lisette Oropesa, es una de las sopranos más queridas por el público de Madrid, en el cual tiene muchos seguidores. Desde su consagración en 2018 con aquella memorable Lucia di Lammermoor, ha deleitado a los madrileños con Traviata, Il Turco in Italia, y ahora esta Maria Stuarda que está entre sus mejores interpretaciones en la capital. Uno podría pensar a priori que su voz de coloratura no es la que demanda la partitura, pero Oropesa ha realizado uno de los mayores esfuerzos de su carrera para cumplir con la parte y el resultado ha sido un éxito. Su bella y dulce voz, sumada a sus agudos impresionantes, y su interpretación entregada del personaje, que ayudó especialmente en el grave; resultaron en una versión memorable. Cuando estaba en escena, no podía apartarse la vista de ella. A medida que transcurría el acto final, Oropesa subía el nivel, y de hecho el final fue conmovedor, tanto en el aria de oración, como en la escena siguiente, donde recibió aplausos espontáneos y en la cabaletta final "Ah, se un giorno", donde estuvo espléndida, cerrando con un sobreagudo espectacular. Una vez más, este ruiseñor latino ha conquistado a su público.

Frente a ella, una mezzosoprano emergente: la rusa Aigul Akhmetshina, un nombre en alza en el mundo de la ópera, ha impresionado con su poderosa voz, interpretando a Isabel I de Inglaterra. Akhmetshina tiene un timbre muy oscuro, contraltado, una voz que suena carnosa, con un impactante volumen y un grave apreciable. Algunos dicen que su dicción podría ser mejorable, pero lo que está claro es que sus medios vocales impresionan, y de seguir trabajándolos, podría convertirse en una de las mezzosopranos más importantes de nuestra época. Ya había cantado en 2021 en Madrid en el segundo reparto de Cenerentola, pero esta interpretación la ha consagrado para el público capitalino. Durante toda la función mantuvo un nivel espléndido, mejorando aún si cabe en su breve intervención en el tercer acto. Esperamos volver a verla pronto en el Real.

Ismael Jordi interpretó al conde Leicester. Jordi ya está en una fase de madurez vocal, que le pasa factura en el agudo, especialmente en el primer acto. Aunque breve en comparación con los anteriores, el rol de Leicester es intenso, y necesita un tenor de nivel, como Jordi, para sacarlo adelante. Pero aún le quedan recursos: por ejemplo, unos bellos pianissimos en el dúo del primer acto con la reina Isabel, y su interpretación fue a más, entregado en la gran escena final.

Espléndido en todo momento estuvo Roberto Tagliavini como Talbot. Este bajo italiano, habitual en el Real, interpretó brillantemente al amigo de María, con su potente voz y su espectacular grave.

El joven barítono polaco Andrzej Filończyk fue un notable Lord Cecil, especialmente en el tercer acto, y la mezzosoprano Elissa Pfaender una bien cantada Anna Kennedy.

En una ópera belcantista, si el reparto es de nivel, como en este caso, la representación es muy disfrutable, más aún cuando se trata de una ópera que requiere de cantantes de enjundia. Así,esta representación de Maria Stuarda ha sido vibrante, y se ha pasado en un suspiro debido a la intensidad del reparto, con ovaciones por cada intervención de Oropesa y Akhmetshina, y tras el final de la obra, a todo el elenco. Al salir del teatro, varios espectadores se dirigían a la salida de artistas para saludar a Oropesa. Posiblemente, nos encontremos ante el mayor éxito de la temporada.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.

sábado, 21 de diciembre de 2024

Ballet clásico en navidad: La Sylphide en el Teatro de la Zarzuela.

Madrid, 20 de diciembre de 2024.

De ella dicen que es el ballet más viejo del repertorio clásico, y la coreografía más antigua que se conserva completa. La Sylphide, fue primero coreografiada en París en 1832 por Filippo Taglioni con música de Jean Schneitzhoffer (versión hoy perdida), y después por Auguste Bournonville, con música de Herman Severin Løvenskiold, para su estreno en la Ópera Real de Copenhague en 1836. Esta versión, desde entonces, se ha convertido en uno de los ballets más programados en todo el mundo.

La historia del tenor Adolphe Nourrit es muy propia del Romanticismo, ambientada en Escocia, un destino recurrente en la ficción de esta época, en la que una sílfide, una criatura del bosque, enamora al joven James, olvidándose de su prometida Effie, por ella, pero los hechizos de la malvada bruja Madge echarán todo a perder. Prima hermana de otro gran clásico, Giselle, esta obra tiene elementos sobrenaturales y dramáticos, además del componente folklórico que le daba un destino lejano (para los lectores de esa época) como Escocia.

Si las navidades siempre han sido sinónimo de ballet, estando de hecho vinculadas a "El Cascanueces" de Tchaikovsky, que se ofrece cada invierno, a cargo de compañías privadas, primero rusas y ahora ucranianas, en las grandes ciudades de España; la Compañía Nacional de Danza, en los últimos años ha programado espectáculos de danza clásica, casi siempre por navidades. En el Teatro de la Zarzuela, han presentado clásicos como Don Quijote, El Cascanueces, Giselle y el año pasado esta Sylphide, que ahora vuelve al Teatro de la Zarzuela, ahora bajo la dirección artística de Muriel Romero, con una puesta en escena de la danesa Petrusjka Broholm, experta en Bournonville.

Una de las cosas que más me enervan de cuando veo ballet, es que el reparto del día no se publique. Ya bastante duro es sufrirlo en las compañías privadas, pero ahora he tenido de nuevo que adivinar quién interpretaba a quién, algo sorprendente para mí ya que las pocas veces que he visto un ballet en un gran teatro, los repartos venían publicados al menos en el programa de mano.

Esta noche, la pareja protagonista ha estado interpretada por Giada Rossi como la sílfide y Alessandro Riga como James, ambos lo más entregados posible. Rossi ha estado impecable, dando muestras de agilidad, controlando la coreografía especialmente en el complicado segundo acto. Riga, en cambio, fue de menos a más conforme avanzaba la función, pero estuvo al mismo buen nivel que Rossi, en las escenas de las danzas de las sílfides.

Felipe Domingos fue un excelente Gurn, ágil, vigoroso, veloz, que le robaba el protagonismo a James y toda la escena en general cuando salía. Martina Giuffrida fue una muy buena Effie, e Irene Ureña interpretó a la perversa bruja Madge, una bella y misteriosa mujer en esta versión.

La música de Løvenskiold es como si fuera belcanto pero en ballet. La encargada de interpretarla en esta ocasión es la Orquesta del Teatro de la Zarzuela, dirigida por Daniel Capps. La funcional música describe momentos a veces dramáticos, como la trompa que da inicio a la obertura, o el violonchelo en el inicio de la segunda escena del segundo acto, que recrea un ambiente mágico, algo en lo que el violonchelista francés Stanislas Kim brilló intensamente.

La puesta en escena de Broholm tiene una bella escenografía a cargo de Elisa Sanz, con una amplia casona escocesa en el primer acto y un precioso bosque en el segundo, y un vestuario clásico a cargo de Nicolás Fischtel, destacando los trajes escoceses del primer acto.

Es loable que una compañía de danza española al fin programe al menos un título al año de ballet clásico, que siempre gusta al gran público y que agota localidades. Pero un título al año no crea tradición, ni para el público ni para los que quieren dedicarse al ballet, que tienen que ir al extranjero para cumplir sus sueños. Ojalá algún día se consiga en nuestras grandes ciudades: si las compañías privadas rusas y ucranianas tienen éxito, los grandes teatros, con mejores medios, podrían sentar las bases de una afición futura.

Con el entusiasmo navideño, el Teatro de la Zarzuela ha vuelto a apuntarse otro éxito, pues todos los días se cuelga el cartel de "no hay billetes" y pueden verse muchas familias entre el público. Además de la parafernalia en las calles con el iluminado de las mismas y las multitudes de compras, con el ballet clásico se siente la navidad en el teatro de la calle Jovellanos.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.

lunes, 16 de diciembre de 2024

Hans Pfitzner, el compositor problemático: Palestrina en streaming desde Viena, dirigida por Thielemann.

No hay muchas oportunidades hoy en día de ver alguna música del compositor alemán Hans Pfitzner en teatros de ópera y salas de conciertos. De hecho, si ocurre, se suelen reducir a los tres preludios de su ópera "Palestrina", su obra más conocida hoy en día. Y si esta ópera se representa, suele ser principalmente en algún país germánico. Pero ni siquiera esto es tan frecuente en el repertorio como quisiéramos. Y esto se debe a dos principales razones:

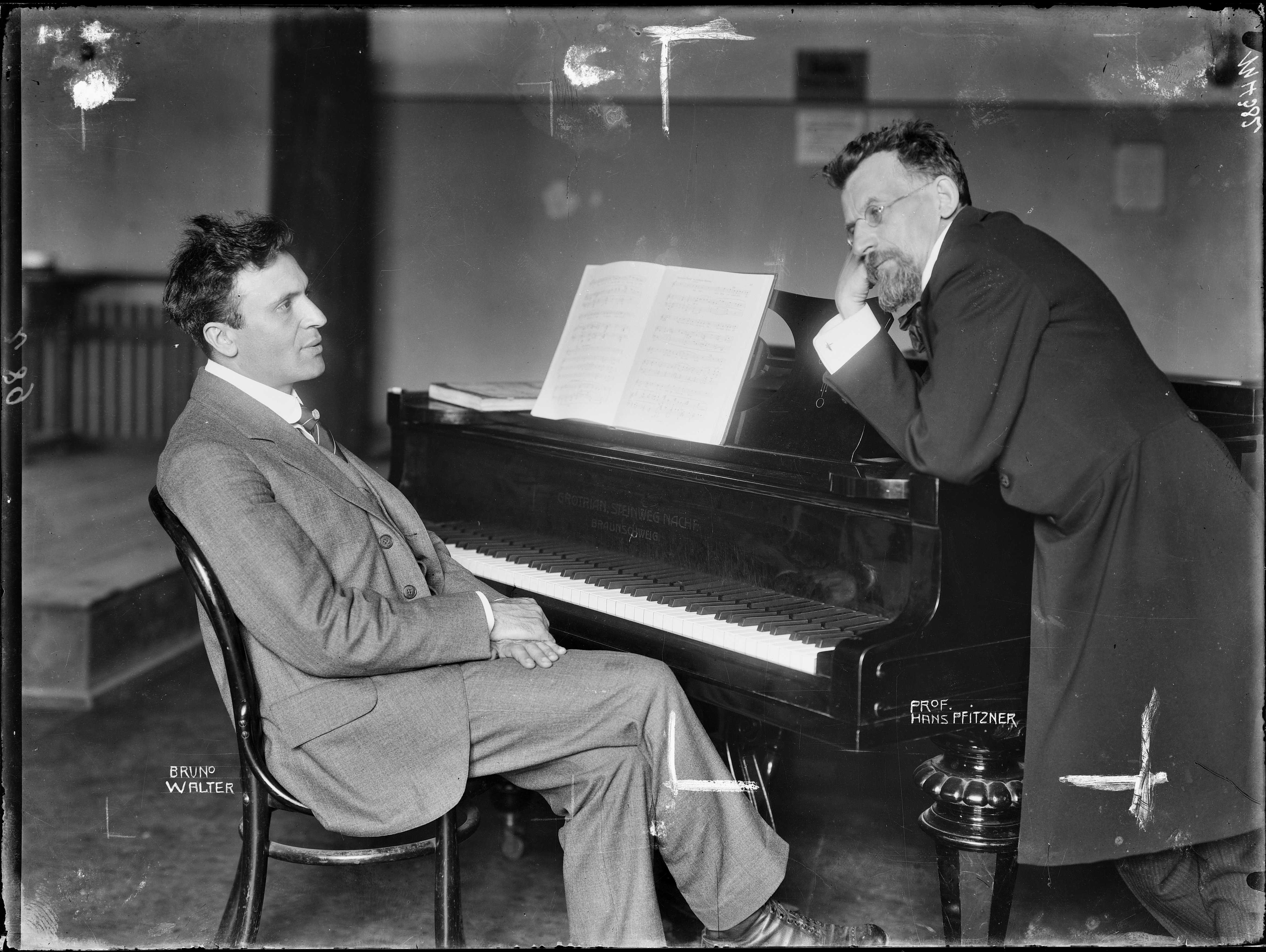

El primero y el de sobras conocido, es que simpatizó con los nazis. Ya desde su juventud, el temperamental Pfitzner era abiertamente antisemita. Incluso tuvo la poca delicadeza de decirle a un amigo judío que se había formado como antisemita durante su juventud en Berlín. Esto no le impidió tener amigos y valedores judíos como Bruno Walter, quien estrenó esta ópera. El también judío Selmar Meyrowitz estrenó la bellísima y hoy olvidada cantata Von Deutscher Seele (Del alma alemana, basada en poemas de Eichendorff), de 1922. Pfitzner creía que algunos "nobles" judíos eran lo suficientemente patriotas como para ser alemanes honorables. Esto es algo que más adelante le traería problemas. A principios de los años 20, Adolf Hitler le visitó en el hospital, y tras discutir con él este tema, el dictador se decepcionó tanto que le hizo la cruz, llegando a creer que era medio judío, lo que para él era inadmisible. Aunque durante el período nazi sus obras fueron favorecidas, Pfitzner no obtuvo el reconocimiento en vida que esperaba, en parte por esa "acusación" que le forzó a probar que su linaje era gentil. Fue también forzado a jubilarse y su pensión no fue la esperada. De hecho tuvo que recurrir a buscar la amistad de altos cargos nazis para poder prosperar, especialmente del infame Hans Frank, gobernador general de Polonia durante la invasión nazi de ese país, y responsable de la muerte de millones de personas inocentes.

Aunque terminó por oponerse a ciertas cosas de los nazis, incluso a rechazar componer una nueva música para "El Sueño de una noche de Verano", ya que la del judío Mendelssohn estaba prohibida, el fin de la guerra no le supuso un cambio. Llegó a escribir que "La judería mundial es un problema y, de hecho, un problema racial, pero no sólo uno, y se retomará, por lo que la gente recordará a Hitler y lo verá de manera diferente que ahora (...) fue su proletismo innato lo que le llevó a asumir el puesto de exterminador llamado a destruir cierto tipo de insecto, ante el más difícil de todos los problemas humanos. Así que no se le debe culpar por el "por qué", ni por "que lo hizo", sino sólo por el "cómo" abordó la tarea (...) La historia mundial ya ha visto que una raza humana puede ser exterminada de la superficie de la tierra, con el exterminio de la originalmente magnífica raza india […]. En términos de moral internacional y costumbres de guerra, Hitler realmente podría sentirse "cubierto" por este único ejemplo; el "cómo" de estos actos de violencia y métodos de opresión es, por supuesto, condenable en sí mismo, siempre que se base en la verdad y no se exagere deliberadamente. Es posible que en los campos de concentración hayan ocurrido cosas terribles, como siempre suceden en esos períodos de agitación, como casos aislados y por parte de brutos subalternos, como suceden siempre y en todas partes, pero menos aún entre el pueblo alemán. Pero si nosotros, los alemanes, quisiéramos hacer un cálculo contrario de las atrocidades que se cometieron contra nosotros [...], la relación entre culpa y acusación de crimen y función judicial cambiaría enormemente y se invertiría."

¿Pretendía Pfitzner insinuar con esto que si desaparecieron los "indios" americanos, los judíos podían hacerlo? Toda desaparición de un grupo étnico es una tragedia para la humanidad, no un "ejemplo". Aunque fue absuelto en su proceso de desnazificación, la reputación de Pfitzner quedó irremediablemente manchada hasta nuestros días, siendo esta categorización como músico "nazi" el principal obstáculo para su mayor y merecida presencia en las salas de conciertos en todo el mundo. Aunque su música se siguió interpretando en Alemania y Austria, e incluso desde los 80 y 90 del siglo pasado y su música se ha interpretado y grabado cada vez más; casi siempre es solo en países germanoparlantes.

El segundo y no menos importante motivo, es que Pfitzner se declaró abiertamente antimodernista, viviendo en una época donde la música sinfónica y vocal vivía una época de constante efervescencia y experimentación. De hecho, él se consideraba defensor de la tradición musical alemana. Su conservadurismo musical contribuyó a que su fama se limitase principalmente a Alemania y Austria. Su música (y esto es algo que también ocurriría con compositores de menor renombre favorecidos durante el nazismo) es muy bella, suma, pero no aporta nada nuevo si la comparamos con la de otros colegas más célebres. Por ejemplo, Von Deutscher Seele es una cantata hermosa, con momentos inspirados, pero no considero que se compare con los Gurrelieder ni con la Segunda Sinfonía de Mahler. El concierto para violín op. 34, el concierto para violonchelo op. 42, la sinfonía "An der Freude", las canciones orquestales, o la suite musical de la obra teatral Das Kätchen von Heilbronn son algunas de sus obras que merecerían estar en salas de conciertos de forma más asidua. Sin embargo, pese a su complejidad, riqueza orquestal y gran belleza, el impacto de su música poco tiene que hacer frente al de las obras de Richard Strauss, Britten, Stravinsky o Shostakovich.

Palestrina fue estrenada en 1917, con un enorme éxito, y permaneció en el repertorio hasta después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Considerada como una "leyenda musical", Pfitzner se compara con Palestrina: la Santa Sede debate, entre otros asuntos, el prohibir la polifonía, un símbolo de la secularización, y que había supuesto una innovación en la música sacra, para volver a la "pureza" del canto gregoriano. Palestrina defiende su arte, de la élite, de venderse al poder que, representado en el Cardenal Borromeo, le coacciona para componer una misa que le permita salvar la polifonía. Él prefiere la inspiración, y antes que ser obligado, prefiere no componer. Pfitzner pretende defender su arte conservador de los "peligros" de la modernización de la música, tan aceptados por la élite cultural. Y como Palestrina tras perder a su esposa, algo que influye en su pérdida de inspiración, Pfitzner se convierte en un ermitaño social debido a las tragedias de su vida, cuyo colofón será perder a todos sus hijos tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial, aunque esto ocurriría años después del estreno de esta ópera. El acto segundo de la obra transcurre en el concilio de Trento, donde nadie se pone de acuerdo en nada, y al final el gran conflicto que acaba en riña es reprimido con ejecuciones y torturas. Hay mucha influencia de la obra de Wagner, el primer acto es deudor de Parsifal, especialmente en la primera obertura, donde se escucha el motivo principal de la obra. En general, la partitura desprende una gran belleza y colorido musical, así como una elaborada e interesada orquestación. El segundo acto, con tanta discusión, puede recordar que Tannhäuser o los Maestros Cantores, pero como bien dijo Pfitzner, sin motivo para la risa. El tercer acto es bello musicalmente, pero sin la inspiración del primero. La obra termina con una breve reflexión del músico antes de que se ponga a tocar el órgano, cerrando la obra con el motivo principal de la obertura.

Un compositor tan problemático necesita de una iniciativa para programarse hoy en día. Y el principal valedor de Palestrina en la Europa actual es el maestro alemán Christian Thielemann, con fama de conservador hasta en lo que no es musical. Hace casi 30 años, dirigió esta ópera en Londres y Viena. Ahora, 23 años después de sus últimas funciones en la capital austríaca, regresa este título de la mano de Thielemann, en la misma producción de Herbert Wernicke, que se vio hace décadas en ese mismo escenario. Ahora, para la posteridad, la función del 12 de diciembre queda inmortalizada en el streaming. Hasta ahora, solo existía un vídeo de esta ópera, procedente de Múnich en 2009, pero si esta filmación se convierte en DVD, se convertirá en el vídeo de referencia y la grabación más importante de esta ópera en el siglo XXI.

La puesta en escena de Wernicke sitúa la ópera en lo que parece un auditorio musical blanco, con un gran órgano de tubos presidiendo el escenario e instrumentos de orquesta con atriles y partituras. En el centro hay una mesa en la que Palestrina compone sus obras y a la izquierda hay un pequeño órgano de iglesia. La puesta en escena sitúa la acción en una época contemporánea y Palestrina aparece como un visible alter ego de Pfitzner y personajes vestidos con trajes modernos. Durante el gran final del primer acto, Palestrina tomará asiento y compondrá la famosa "Misa del Papa Marcello", y las apariciones aquí aparecen como coristas con hábito de iglesia. Su esposa Lucrecia aparecerá con un vestido rojo, como una famosa diva de la ópera. El órgano se abre para revelar un gran coro, los ángeles dictando a Palestrina la música. El segundo acto se abre en la misma sala, pero en lugar del órgano de tubos se ven los asientos, desde donde la aristocracia observa el Concilio. El coro se divide entre cardenales y los partidos español e italiano, vestidos con ropas policiales y militares. Al final, se produce una gran pelea, a la que el ejército responde disparando contra los combatientes. En el tercer acto, volvemos a ver los instrumentos y el gran órgano de tubos. Como momento destacable, el Papa Pío IV aparece en el palco real del teatro, como una divinidad ante la que Palestrina, Ighino y el coro en escena se arrodillan. La ópera termina con Ighino tocando el órgano y un Palestrina cansado y frágil que toma la partitura y comienza a dirigir la orquesta, mientras cae el telón.

El conocimiento que Thielemann tiene de esta ópera se nota en su espectacular dirección, una de las mejores que he visto de él en cualquier grabación. Su estilo de dirección, tan lento, tan majestuoso, tan germánico, hace que aquí cada instrumento brille y suene lírico, ya que se trata de una ópera sobre un conflicto personal. Thielemann transmite su dominio de la música de Pfitzner a la Orquesta de la Ópera de Viena, cuyos instrumentos suenan inspirados, ya que su estilo de dirección encaja con lo que Pfitzner quería transmitir en su música. El famoso preludio del primer acto suena lento, elegíaco, místico, el preludio del segundo acto es apasionado, espectacular, y el preludio del tercer acto suena como la hermana seria y tranquila del Preludio del tercer acto de los Maestros Cantores de Wagner. Las cuerdas (especialmente los violonchelos durante la inspiración de Palestrina en el primer acto), las flautas, los metales en el segundo acto... todos los instrumentos suenan increíbles. El coro también canta muy bien.

Además de su gran orquesta y coro, esta ópera requiere de un gran elenco: un tenor principal, seguido de papeles difíciles para bajos y barítonos.

Michael Spyres canta el papel principal: este tenor, que en los últimos años ha interpretado papeles de Wagner, tiene una voz de barítono (ya que solía ser baritenor en las óperas de Rossini y Bellini) que retrata a un Palestrina deprimido y cansado, desesperado por no estar inspirado y afligido por su esposa muerta. Su actuación transmite la de un hombre que envejece prematuramente y que solo quiere mantener su libertad para crear. Las mujeres son cantantes consumadas: Kathrin Zukowski es un dulce Ighino, hijo de Palestrina, así como Patricia Nolz, en el rol de Silla, aprendiz del compositor, que cantó bien. Wolfgang Koch es el cardenal Borromeo de temperamento fuerte, con una voz madura, no siempre profunda en el sonido, pero que aún así muestra un buen canto. El tenor de carácter Michael Laurenz es un cardenal Novagerio de voz potente, que suena aquí como un personaje intrigante y grotesco, así como Hiroshi Amako como el obispo de Abisinia. Michael Kraus también ha cantado bien el papel del cardenal de Lothringen. Günther Groissböck canta maravillosamente y su imponente presencia es adecuada para el papel del Papa Pío IV, en uno de los momentos más mágicos de la actuación.

Al tratarse de una ópera poco representada, esta representación ha sido todo un acontecimiento en el mundo musical de habla alemana. Tal entusiasmo se percibe en las ovaciones extraordinarias al final de cada acto.

La obra de Pfitzner, con sus más y sus menos, merece tener más presencia en las programaciones sinfónicas, y Palestrina una ópera que debería verse más a menudo, en todos los grandes teatros debido a su belleza. Pero de su escasa programación actual, solo hay un responsable: el propio Hans Pfitzner.

Porque lo que este hombre amargado sembró en vida con sus ideas musicales y su antisemitismo y servilismo para los nazis, su obra musical lo ha recogido en forma de olvido en nuestros días. Qué pena.

Aquí, uno se puede hacer una idea de esta ópera.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.

Hans Pfitzner, amazing composer, umpleasant man: Thielemann conducts a dazzling Palestrina in Vienna.

There are not many chances today to see some of Hans Pfitzner's music in opera houses and concert halls. In fact, if it happens, they are usually limited to an orchestra playing the three preludes to his opera "Palestrina", his best-known work. And if this opera is performed, it is usually done in Germany, Austria or Switzerland. But even in this case, this is not very frequent. Maybe, because of two main reasons:

The first and well-known one is that Pfitzner sympathized with the Nazis. From his youth, the bad-tempered Pfitzner was openly anti-semitic. He even had the indelicacy to tell a Jewish friend that he had been trained as an anti-semite during his youth in Berlin. This did not prevent him from having Jewish friends and supporters like Bruno Walter, who premiered this opera in 1917. Another jew, Selmar Meyrowitz, premiered the beautiful (now forgotten) cantata Von Deutscher Seele (From the German Soul, based on poems by Eichendorff), in 1922. Pfitzner believed that some "noble" Jews were enough patriotic to be honorable Germans. This is something that would cause him some problems later. In the early 1920s, Adolf Hitler visited him in the hospital, and after discussing this issue with him, the future dictator was so disappointed that he didn't want to have anything to do with him, even he believed that Pfitzner was half-Jew, which for him was unacceptable. Indeed, Pfitzner had to prove his Gentile ancestry. Although during the Nazi period he was one of the most favored and scheduled musicians in operatic and symphonic venues, Pfitzner did not obtain the recognition in life that he expected. He was forced to retire and his pension was not very high. In fact, he had to resort to seeking the friendship of senior Nazi officials in order to thrive. Notorios was his friendship to the infamous Hans Frank, General Governor of the Nazi-occupied Poland, and responsible for the deaths of millions of people. During the war, he conducted in occupied countries such as Poland and France, where he attended a Palestrina performance in 1942.

Despite that he didn't agree with the nazis completely, even he rejected to put music to Shakespeare's A Midsummer night's dream because Mendelssohn's music was banned, the end of the war did not bring about a change for him. He went so far as to write that "World Jewry is a problem and, in fact, a racial problem, (...), and it will be taken up again, so people will remember Hitler and he will be seen differently that he is now (...) it was his innate proletarianism that led him to assume the position of an exterminator called to destroy a certain type of insect, in the face of the most difficult of all human problems. So he should not be blamed for the "for what", nor by "that he did it", but only by "how" he approached the task (...) World history has already seen that a human race can be exterminated from the surface of the earth, with the extermination of the originally magnificent Indian race […]. In terms of international morality and customs of war, Hitler could really feel "covered" by this single example; the "how" of these acts of violence and methods of oppression is, of course, condemnable itself, as long as it is based on truth and not is deliberately exaggerated. It is possible that terrible things have happened in the concentration camps, as they always happen in these periods of unrest, as isolated cases and by subaltern brutes, as they always and everywhere happen, but even less so among the German people. But if we, the Germans, wanted to make a contrary calculation of the atrocities that were committed against us [...], the relationship between guilt and accusation of crime and judicial function would enormously change and be reversed."

Was Pfitzner trying to imply since the Native "Indians" in the Americas disappeared, then Jews could do it too? Any disappearance of an ethnic group is a tragedy for humanity, not a "single" example. Although he was acquitted in his denazification process, Pfitzner's reputation remained irremediably stained to this day, this categorization as a "Nazi" musician being the main obstacle to his greater and deserved presence in concert halls. Pfitzner, having lost his family during the war, died in 1949 in Salzburg, aged 80.

The second and no less important reason is that Pfitzner openly declared himself an openly anti-modernist, living in a time when symphonic and vocal music was experiencing a period of constant effervescence and experimentation. In fact, he used to consider himself a custodian of German musical tradition. As a result, his fame was specially limited to the German-speaking world. His music (and this is something that would also happen with less renowned composers favored during Nazism) is very beautiful, it adds, but it does not contribute anything new, despite its complex, rich musical language. For example, Von Deutscher Seele is a beautiful cantata, with many inspired moments, but its impact couldn't reach those ones from masterpieces such Schoenberg's Gurrelieder or Mahler's Second Symphony. Another Pfitzner's amazing works are the violin concerto op. 34, the cello concerto op. 42, the symphony op. 46"An der Freude", the orchestral lieder, the overtures from operas such as Der Arme Heinrich or Das Christelelflein, or the musical suite for the theatrical play Das Kätchen von Heilbronn, are some of his works that do deserve to be in concert halls more frequently, although most of them did not have the same musical impact as the symphonic poems of Richard Strauss, or the music of Britten, Stavinsky or Shostakovich. Even when his work has been more performed and recorded (Werner Andreas Albert's recordings for the CPO label are an example) from the 80s and 90s, it mostly seems to happen mainly in Germany and Austria.

Palestrina was premiered in 1917, with enormous success, and remained in the German repertoire even until few decades after World War II. Considered a "musical legend", Pfitzner compares himself to Palestrina: the Holy See debates, among other issues, banning polyphony, a symbol of secularization, and which had been an innovation in sacred music, to return to " purity" of Gregorian chant. Palestrina defends his art, from the elite, from selling himself to the power that, represented in Cardinal Borromeo, coerces him to compose a mass that allows him to save polyphony. He prefers inspiration, and rather than being forced to compose. Pfitzner aims to defend his conservative art from the "dangers" of the modernization of music, so accepted by the cultural elite. And like Palestrina after losing his wife, something that influences his loss of inspiration, Pfitzner became an embittered social hermit due to the tragedies of his life, although this would happen after 1917. The second act takes place at the Council of Trent, where no one agrees on anything, and in the end the great conflict that ends in a fight is repressed with executions and torture: a prophetic allegory of what will take place in Germany during Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. There is a lot of influence from Wagner's work, the first act is musically indebted to Parsifal, especially in the first overture, where the main motif of the work is heard. The first act is undoubtedly the most beautiful. Afterwards, there are moments of great beauty and musical color, alternating with others of the same kind. Still, the orchestration, as several have pointed out, is quite interesting. The second act, with so much discussion, may remind us of Tannhäuser or the Meistersinger, but as Pfitzner rightly said, without reason for laughter. The third act is beautiful musically, but without the inspiration of the first. The work ends with a brief reflection by the musician before he begins to play the organ, closing the work with the main motif of the overture.

Such a problematic composer's musical legacy needs an initiative to have it performed today. And Palestrina's main supporter in present day's Europe is the German maestro Christian Thielemann, with a reputation for being conservative beyond the music. Almost 30 years ago, he conducted this opera in London and Vienna. Now, 23 years after its last performances in the Austrian capital, this title returns to the Vienna Opera conducted by Thielemann, in the same production by Herbert Wernicke, which was seen decades ago on that same stage. Now, for posterity, the December 12 performance is immortalized in streaming. Until now, there used to be only one video of this opera, coming from Munich in 2009, but if this recording becomes a DVD, it will become the referential video and the most important recording of this opera in 21st Century.

Wernicke's staging sets the opera in what it seems a white musical auditorium, with a big pipe organ presiding the stage, and orchestral instruments with music stands and scores. In the middle, there is a table in which Palestrina composes his works, and at the left there is a small church organ. The staging sets the action in a contemporary era, and Palestrina appears as a visible Pfitzner's alter-ego, and characters dressing in modern suits. During the big Act One finale, Palestrina will take seat and compose the famous "Pope Marcello Mass", and the aparitions are actually choristers. His wife Lucrezia will appear in a red dress, as a famous operatic diva. The organ opens to reveal a big choir, the angels dictating Palestrina the music. Act Two opens in the same hall, but instead of the pipe organ, stalls are seen, in which aristocracy will attend the Council. The chorus is divided between cardinals and the Spanish and Italian parties, dressed in police, military customs. At the finale, there is a big quarrel, to which army stops by shooting the fighting people. In Act 3, we see again the instruments and the big pipe organ. As a remarkable moment, Pope Pius IV appears in the Royal Box, like a divinity to which Palestrina, Ighino and the chorus on stage kneel before. The opera ends with Ighino playing the organ and a tired, frail Palestrina taking the score and starting to conduct as the curtain falls.

Thielemann's knowledge of this opera is noticeable by his amazing conducting, one of the best I have seen from him in any recording. His conducting style, so slow, so majestic, so Germanic, here makes every instrument to shine and to sound lyric, as this is an opera about a personal conflict. Thielemann conveys his command of Pfitzner's music to the Vienna Opera Orchestra, whose instruments sound inspired, beautiful, as his style of conducting fits on what Pfitzner wanted to convey in his music. The famous Act One prelude sounds slow, elegiac, mystical, Act Two prelude is passionate, spectacular, and Act Three prelude sounds as the serious and calm sister of Meistersinger's Prelude to Act 3. Strings (specially cellos during Palestrina's inspiration in Act 1), flutes, the brass in Act Two, all sound amazing. The Chorus sings very well too.

Apart from its big orchestra and chorus, this opera requires from a big cast: a leading tenor, followed by difficult roles for basses and baritones.

Michael Spyres sings the title role: this tenor who is doing Wagner roles in recent years, has a baritonal voice (as he used to be a bel canto baritenore for Rossini and Bellini operas) which portrays a depressed, tired Palestrina, in despair for not being inspired and grieving his dead wife. His acting conveys an early aging man who wants his freedom to create. The females are accomplished singers: Kathrin Zukowski is a sweet Ighino, as well as Patricia Nolz as a well sung Silla. Wolfgang Koch is the strong-tempered Cardinal Borromeo, with a matured voice, not always deep in sound, but still showing good singing. Spieltenor Michael Laurenz is a big-voiced Cardinal Novagerio, sounding here as a Mime-like scheming and grotesque character, as well as Hiroshi Amako as the Abisinia Bishop. Michael Kraus has also sung well the role of the Lothringen Cardinal. Günther Groissböck sings beautifully and his imposing presence is suitable for the role of Pope Pius IV, in one of the most magic moments of the performance.

As this is a rarely performed opera, this performance has been quite a big event in German-speaking musical world. Such enthusiasm is perceived in the outstanding ovations at the end of each act.

Pfitzner's work deserves to be more performed by world-class orchestras, and Palestrina is an opera that should be seen more often, in all major opera houses, because of its beauty. But for its current limited programming, apart from the obvious big resources needed, maybe an important reason lies: Hans Pfitzner himself.

Because what this embittered man sowed with his decisiones and some attitudes in his lifetime, his works reaped today through unfair neglection. So sad.

Here, you can make your own opinion of this opera.

domingo, 24 de noviembre de 2024

ESP/ENG Haciendo accesible la profundidad: La Quinta de Bruckner en el Auditorio Nacional.

For English, please scroll down.

Madrid, 24 de noviembre de 2024.

Termina el año Bruckner, y la Orquesta Nacional de España elige una de sus sinfonías más complejas y densas, la Quinta Sinfonía, llamada la Católica por muchos, aunque el maestro la llamó la Fantástica o su obra maestra contrapuntística, dedicada al político Karl von Stremayr. Bruckner no pudo oírla en vida, ya que estaba muy enfermo para ir al estreno en 1894. De hecho, moriría dos años más tarde en 1896. La Quinta es una obra dura incluso para muchos brucknerianos. De dimensión wagneriana pero no tan majestuosa como la octava, íntima pero no tan hermosa como la séptima, oscura pero no tan conflictiva como la novena. Es una obra que parece venir de las profundidades del pensamiento del compositor, incluso si no renuncia a la lentitud, la densidad y la majestuosidad, muchos momentos son más bien oscuros, elegíacos, como el inicio del segundo movimiento. Esta peculiaridad la sitúa en un lugar especial, en la fase intermedia que hay entre la cuarta y la séptima sinfonías, aunque tiene una similaritud en densidad y longitud con la todopoderosa octava.

Para no ser un músico tan popular en los públicos españoles, este año se ha programado bastante por razón de su nacimiento. En Madrid, la Orquesta de RTVE ha interpretado la sexta y una séptima dirigida magistralmente por Christoph Escenbach, y la Orquesta de la Comunidad de Madrid ha interpretado la Misa nº2. La Nacional de España ha interpretado las sinfonías octava, séptima y ahora la quinta.

Tal obra difícil requiere de una orquesta capaz de lidiar con la fuerza de esta obra. Y la Orquesta Nacional de España es la mejor disponible para tal cometido. Tras haber dirigido una memorable versión de la Octava Sinfonía en enero, Afkham aborda de nuevo una partitura del maestro de Ansfelden. Y el resultado ha sido tan bueno que ha conseguido más accesible una obra que suele ser lo contrario. Los tempi han sido un poco lentos, especialmente al principio, pero lo suficiente para paladear poco a poco la riqueza orquestal de la obra. Uno no deja de sorprenderse con los brillantes sonidos de la orquesta, de este modo, los violines han sonado espléndidamente en el segundo movimiento, así como la madera: el clarinete respondiendo con un firme sonido después del ataque orquestal al inicio del cuarto movimiento. Afkham ha conseguido transmitir los estados de ánimo de la obra, por medio de una brillante interpretación de cada una de las secciones de la orquesta.

No estaba lleno el auditorio, pero se podía apreciar, y esto en Bruckner es una alegría, varios jóvenes, y algunos niños. Uno piensa que hay esperanza después de todo: para el brucknerismo, y para la vida musical en el futuro.

miércoles, 20 de noviembre de 2024

The feminist, empowered martyr: Handel's Theodora at the Teatro Real.

Many years ago I read, I can't remember where, or maybe I heard about, that during a performance of Verdi's Otello more than sixty or seventy years ago, the famous tenor who sang its breathtaking finale, took advantage of caressing Desdemona's body, while he was dying next to her. When the curtain came down, Desdemona, sung by a strong-tempered diva, stood up and slapped the lascivious tenor. Nowadays, after so many sexual scandals that have affected the show business, and with greater sensitivity to the subject, there were actresses in Hollywood films and series, who began to demand the services of what is now called an intimacy co-ordinator, who are responsible for ensuring the actors involved not to go beyond what is coreographed while recreating sex scenes.

Why am I talking about all this first? Because the Teatro Real in Madrid has announced. with great fanfare in all social media, that for its new staging of Handel's oratorio Theodora, (which is being performed in November and which was seen at the Teatro Real in 2009 in concert version) they have hired the most famous intimacy coordinator of the moment, the British Ita O'Brien , who has worked on famous series such as Sex Education. O'Brien is a regular collaborator of Katie Mitchell , the director of this Theodora staging, coming from the London Royal Opera House, which sets the action in a modern era. Theodora is an oratorio that Handel premiered in 1750, but despite the composer considered it as one of his best creations, it was not very successful in his lifetime. However, the work has finally enjoyed the popularity it deserves, because of its beautiful music. Like all oratorios it is a static work, in this case it is about the martyrdom of Theodora, a legendary young Christian woman who lived in Alexandria (Antioch in the work) during the time of the Roman Emperor Diocletian (famous persecutor of Christians), and Didymus, a Roman in love with her, who converts to Christianity out of love. A story that the librettist Thomas Morell took from a play.

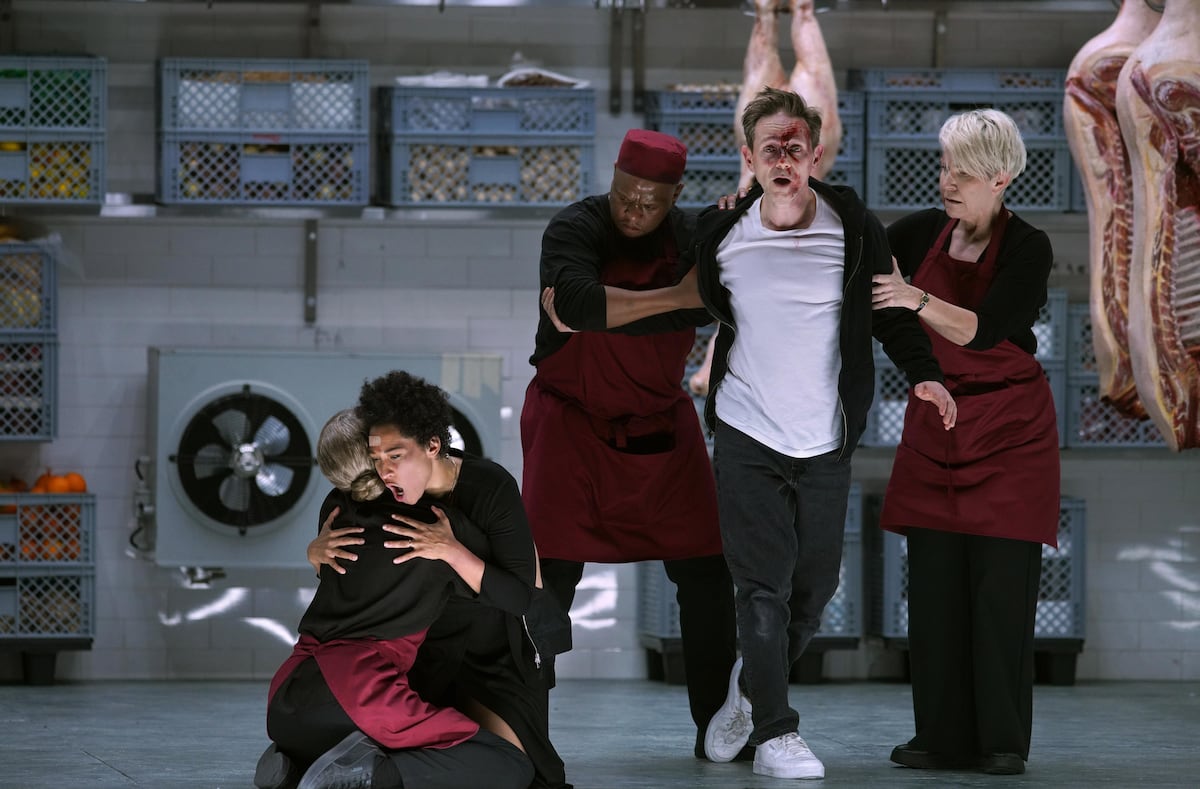

Mitchell's production enhances the staging of this argument, making it more entertaining and interesting. Known for her feminist-oriented works on stage, Mitchell sets the action in a modern era. As an interesting detail, she uses slow motion, here recreated by the singers, to give greater intensity to the emotions described in the music. Theodora is not a young, self-sacrificing, mystical maiden, but an empowered, strong-tempered woman willing to do anything for her faith, thus becoming a feminist reference for today. Christians are the service staff of the Roman embassy in Antioch. Saint Theodora and her friend Irene work as cooks, but at the same time they are radical Christian activists, who even resort to terrorism to combat Roman persecution. Thus, in the large, modern kitchen, they prepare bombs and hide weapons. But they also celebrate Christmas, bringing out a small, illuminated Christmas tree. The production takes place in a very small space, a stage box that moves from one side to the other, revealing the rooms of the embassy. The kitchen and the embassy hall are the main ones. But when the saint refuses to worship Jupiter, she is forced into prostitution.

As she sings her famous aria Angels ever bright and fair the Romans dress her as a prostitute and take her to a red room, with professional table dancers dancing on the bar, who will later help Theodora. To the left, a room with a round red bed is the setting where a Roman soldier tries to rape Theodora, who defends herself with a weapon, but after a while, she is finally raped, something which is not seen, fortunately, on stage. Irene, with an enormous role in the work, is here a kind of leader, priestess, and even at the end of the first act she is in charge of officiating the baptism of Didymus, in a moving, solemn liturgical act, before the soldier goes to free his beloved Theodora.

At the end of the play, the protagonists are condemned to death in the cold storage room next to the kitchen, with a few pigs hanging. But the saint does not die alongside her lover: Mitchell changes the ending: Irene and the Christians save them and kill the Romans, taking the embassy and allowing the couple to escape.

The Teatro Real Orchestra , conducted by Ivor Bolton , gradually improved as the work progressed. After a plain overture, the orchestra gradually acquired a more chamber-like sound, as static as the work itself. After having seen them preparing these pieces during a work session,, the Teatro Real Choir, mastered by José Luis Basso, managed to sound mystical and exciting in the final choruses of each act. In the first chorus, And draw a blessing down, the voices were able to cope with the devilish coloratura, as well as transmitting the mysticism in the finale of the first act, together with their male colleagues. In the chorus that closes the work, O love divine, the male section highlighted their powerful deep voices, transmitting the religious character of the piece, although the women were not far behind. Once again, mission accomplished, and in an excellent way.

Although she was not the protagonist, Joyce DiDonato in the role of Irene was certainly the main attraction and led the cast. In this repertoire she is a true specialist: her velvety voice, whose volume is heard throughout the hall and dominates the repertoire. Her interpretation of the beautiful aria Lord, to Thee each night and day, was undoubtedly the best moment of the night, capable of singing in piano voice and giving a prolonged pianissimo, in a breathtaking moment. And in fact it was the only aria who got an applause.

Julia Bullock was a more discreet Theodora. Despite having a beautiful voice, with a darker tone, she seemed to sing a bit restrained while trying to sound angelic, even her vocal volume seemed to fight with the orchestra. As an actress she was impeccable, and committed to the production, which she shows she knows well.

Iestyn Davies was an excellent Didymus, singing well and mastering the coloratura in the arias, in a character with very beautiful music. Equally notable was the tenor Ed Lyon as his friend Septimius, a tenor who surprised with his high tessitura in the beautiful and very long aria Descend, kind Pity. Callum Thorpe was a big-volumen, dark-voiced Valens, but not so subtle at times. Thando Mjandana as the messenger has a brief, only reciting role, but the voice sounds good.

Despite the much publicity given to the issue of the intimacy coordinator, the truth is that the public came to enjoy a pleasant afternoon of baroque music, and to listen the singing of Joyce DiDonato, so admired in this city. The audience was not disappointed, even though the theatre was not full. In the end, the big winner, apart from DiDonato, was the expected one: Handel's music, in one of the big hits of the current operatic season in Madrid.

La ultrajada santa feminista: Theodora de Händel en el Teatro Real.

Madrid, 17 de noviembre de 2024.

Hace muchos años leí, no recuerdo en qué foro, o tal vez me lo contaron, que durante una función del Otello verdiano hace más de sesenta o setenta años, el famoso tenor que lo interpretaba cantaba la escena final, ante el cadáver de su amada Desdémona, momento el cual aprovechó para sobar todo su escultural cuerpo, mientras agonizaba junto a ella. Al bajarse el telón, Desdémona, encarnada por una diva de las de antes, de fuerte carácter, se incorporó y abofeteó al lascivo tenor. Hoy en día, con tantos escándalos sexuales que han afectado al mundo del espectáculo, incluidas acusaciones a famosos artistas y empresarios, y con una mayor sensibilidad con el tema, en el mundo del cine y de las series de televisión, hubo actrices que empezaron a exigir los servicios de lo que hoy se llama coordinador de intimidad, que son los responsables de que en las escenas de sexo, los actores involucrados no se excedan más allá de lo debido y traspasen la delicada línea entre actuación y abuso.

¿Por qué hablo en primer lugar de todo esto? Porque el Teatro Real de Madrid ha anunciado en todos los medios, que para el montaje del oratorio Theodora, de Georg Friedrich Händel, (que se verá este mes de noviembre y que se vio en el Real en 2009 en versión concierto) se ha contado con los servicios de la coordinadora de intimidad más famosa del momento, la británica Ita O'Brien, quien ha trabajado en series famosas como Sex Education. O'Brien es colaboradora habitual de Katie Mitchell, la directora de escena de esta Theodora, procedente de Londres, que ambienta la acción en una época moderna. Theodora es un oratorio que Händel estrenó en 1750, pero pese a que el compositor la consideraba como una de sus mejores creaciones, no tuvo mucho éxito. Sin embargo, la obra ha gozado al fin de la popularidad que merece, pues su música es bellísima, y aunque como todo oratorio es una obra estática, en esta ocasión sobre el martirio de Teodora, una legendaria joven cristiana que vivía en Alejandría (Antioquía en la obra) en tiempos del emperador romano Diocleciano (famoso perseguidor de cristianos), y de Dídimo, un romano enamorado de ella, que se convierte al cristianismo por amor. Una historia que el libretista Thomas Morell tomó de una obra de teatro.

La producción de Mitchell potencia la escenificación de este argumento, haciéndolo más ameno e interesante. Conocida por su labor feminista en escena, Mitchell ambienta la vida de esta santa en una época moderna. Como dato interesante, recurre al movimiento a cámara lenta, aquí recreado por los cantantes, para darle una intensidad mayor a la acción. Theodora no es una joven doncella mística y abnegada, sino una mujer de carácter dispuesta a todo por su fe, convertida así en un referente feminista para la actualidad. Los cristianos son el personal de servicio de la embajada romana de Antioquía. La santa Theodora, y su amiga Irene, trabajan como cocineras, pero al mismo tiempo son activistas radicales cristianas, que para combatir la persecución romana recurren al terrorismo. Así, en la amplia y moderna cocina, preparan bombas y esconden armas. Pero también celebran la navidad, sacando un pequeño arbolito iluminado. La producción transcurre en un espacio muy pequeño, una caja escénica que se mueve de un lado a otro, revelando las estancias de la embajada. La cocina y el salón de la embajada son lo principal. Pero cuando la santa se niega a adorar a Júpiter, es forzada a prostituírse.

Mientras canta su famosa aria "Angels ever bright and fair" los romanos la visten de prostituta y la llevan a una estancia roja, con bailarinas profesionales de table dance bailando en la barra, las cuales luego auxiliarán a Theodora más adelante. Al lado izquierdo, una habitación con una redonda cama roja es el escenario donde un soldado romano intenta violar a Theodora, que se defiende con un arma, pero aun así al cabo de un rato, logra su atroz cometido, el cual no se ve, afortunadamente, en escena. Irene, con un enorme peso en la obra, es aquí una suerte de lideresa, sacerdotisa, e incluso al final del primer acto se encarga de oficiar el bautizo de Dídimo, en un emocionante acto litúrgico, antes de que el soldado libere a su amada.

Al final de la obra, los protagonistas son condenados a muerte en la cámara frigorífica al lado de la cocina, con unos cuantos cerdos colgando. Pero la santa no muere junto a su amado: Mitchell cambia el final. Irene y los cristianos les salvan y matan a los romanos, tomando la embajada y permitiendo a la pareja escapar.

La Orquesta del Teatro Real, dirigida por Ivor Bolton, fue yendo de menos a más a medida que la obra avanzaba. Tras una obertura sin demasiado brillo, la orquesta fue adquiriendo un sonido más camerístico, tan estático como la obra misma. Tras haberlo visto preparar la obra, el Coro del Teatro Real logró sonar místico y emocionante en los coros finales de cada acto. En el primer coro, And draw a blessing down, las voces pudieron con la endiablada coloratura, así como transmitir el misticismo en el final del primer acto, junto a sus colegas masculinos. En el coro que cierra la obra, O love divine, el coro masculino destacó sus potentes voces graves, transmitiendo el carácter religioso de la pieza, aunque las mujeres no se quedaron atrás. Una vez más, misión cumplida, y de forma excelente.

Aunque no era la protagonista, desde luego Joyce DiDonato en el rol de Irene era el reclamo principal. Y lo cierto es que en este repertorio juega en casa: su voz aterciopelada, que se deja oír y que domina el repertorio. Su interpretación de la bellísima aria Lord, to Thee each night and day, fue sin duda el mejor momento de la noche, capaz de cantar en piano y dar un pianissimo prolongado, en un momento sobrecogedor. Y de hecho fue el único número aplaudido.

Julia Bullock fue una Theodora discreta. Pese a que tiene una bonita voz, de timbre más oscuro, parecía cantar más contenida de lo esperable, incluso su volumen vocal parecía pelearse con la orquesta. Como actriz estuvo impecable, y comprometida con el montaje, que demuestra conocer bien.

Iestyn Davies fue un excelente Didymus, bien cantado y dominando la coloratura en las arias, en un personaje con muy bella música. Igualmente notable el tenor Ed Lyon como su amigo Septimius, un tenor que sorprendió con su tesitura aguda en la bella y larguísima aria Descend, kind Pity. Callum Thorpe fue un Valens de voz grande y con un grave tan potente como no tan sutil por momentos. Thando Mjandana como el mensajero tiene un breve papel que solo recita, pero la voz es buena.

Pese a la sonada publicidad dada al tema de la coordinadora de intimidad, lo cierto es que el público vino a disfrutar de una tarde agradable de música barroca, y de Joyce DiDonato, tan querida en esta ciudad. No salió defraudado el respetable, pese a que no estaba lleno el teatro. Al final, la gran triunfadora, aparte de DiDonato, era la esperada: la bellísima música de Georg Friedrich Händel, en lo que puede definirse como uno de los grandes éxitos de esta temporada.

Las fotografías y vídeos no son de mi autoría, si alguien se muestra disconforme con la publicación de cualquiera de ellas en este blog le pido que me lo haga saber inmediatamente. Cualquier reproducción de este texto necesita mi permiso.

.jpg)