In the current Teatro Real season, which comes closer and closer to its conclusion, there has been a remarkable presence of Russian opera, with an emblematic opera, Eugene Onegin , and now with a beautiful opera, rarely performed outside Russia: The Tale of Tsar Saltan, by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Golden Cockerel" was already seen at the Teatro Real in 2017. Rimsky has achieved absolute glory as a composer with his symphonic works: the universally known symphonic poem Scheherazade, a classic of ballet and symphony orchestras; Capriccio Espagnol, another great symphonic poem; and even the famous "Flight of the Bumblebee," which is part of this opera, is known in its orchestral version. However, he has interesting operas in his work catalogue: The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh , or the two already mentioned above. In these works, the themes covered are fairy tales, stories of legendary figures from Russian tradition, such as Kitezh , or Pushkin poems like The Golden Cockerel and Tsar Saltan. The music is colorful, beautiful, with folkloric touches, and orchestrally rich. This very personal touch also meant that his orchestration of Modest Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, helped establish this brilliant masterpiece in the international operatic repertoire as the most important Russian opera.

I still can't believe, and I am very excited with the fact that Dmitri Tcherniakov, the Russian enfant terrible of operatic stage directing, is back to Madrid after twelve years without seeing a production of his. Mentored by the late Gerard Mortier, during the latter's tenure as artistic director at the Teatro Real, he aroused as much passion among regietheater enthusiasts as he sparkled outrage among the more conservative opera goers with his stagings of Eugene Onegin, Macbeth, and Don Giovanni, the latter a complete deconstruction of the legendary seducer, which drew enormous boos at the premiere and at many performances. I did believe that after Mortier's death in 2014, and after his shameful departure from the Teatro Real a few months earlier, he would never be interested in visiting us again.

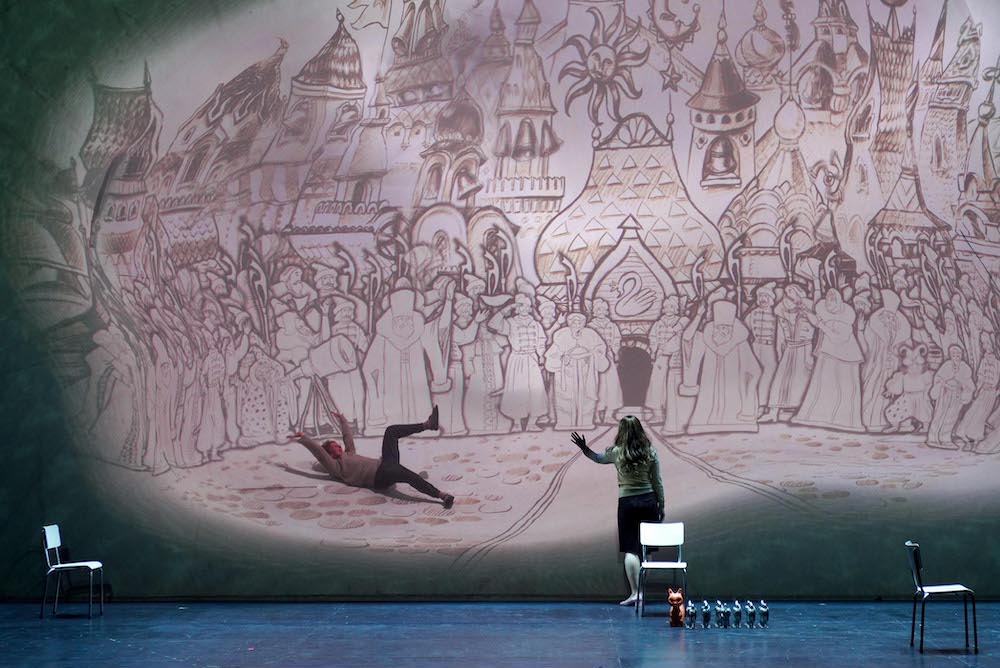

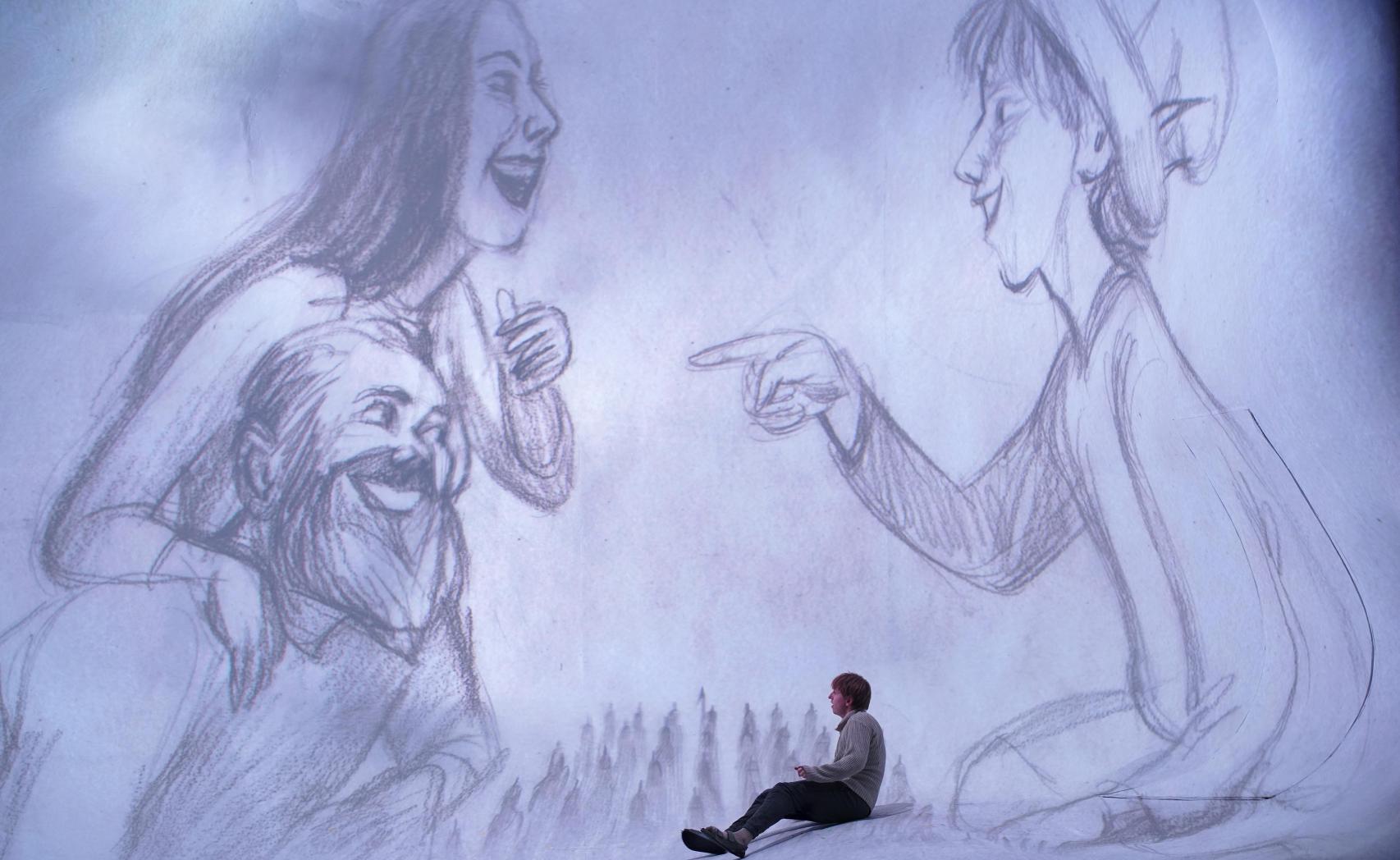

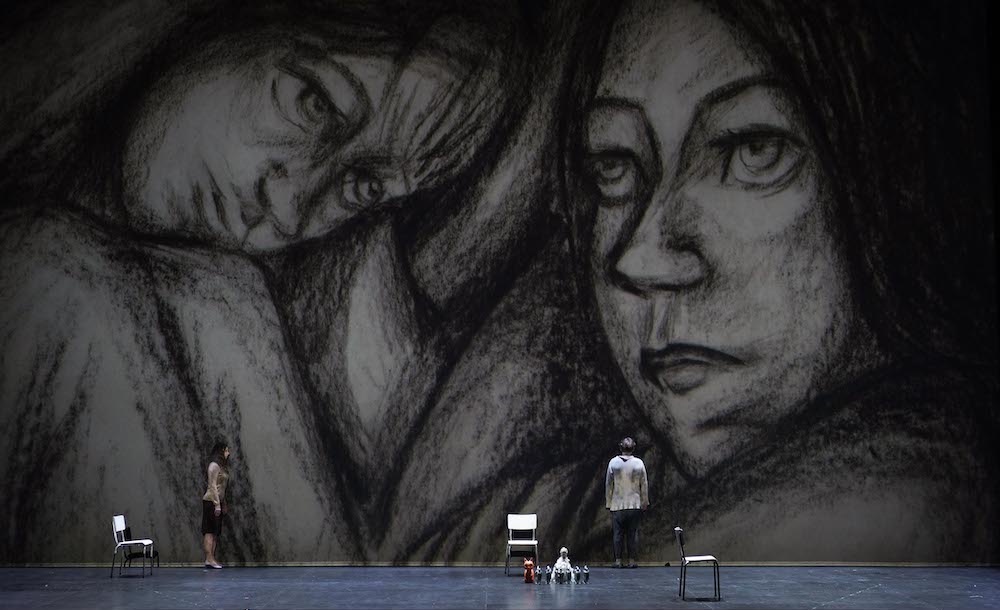

But now he returns, triumphant, with a production of this opera, from Brussels, where it premiered successfully in 2019. Tcherniakov takes a new approach, taking this Pushkin-esque fairy tale and turning it into a drama in which the Tsarina, a single mother, and her son Guidon have been abandoned by the Tsar. Guidon is autistic, and his only reality is the fairy tales his mother tells him, as she is also the only person he speaks to. There is no curtain; instead, there is a room with chairs and a gold-colored wall, and on the stage, some toy soldiers, a squirrel, and a dressed doll, with which Guidon plays while the Tsarina speaks to the audience and tells them that they have been abandoned; that the father doesn't know his son, and that she will tell him everything in the form of a fairy tale. In this way, the story, until the final scene, unfolds like a fairy tale in Guidon's mind. Tcherniakov's regular collaborators, Elena Zaytseva , costume designer, and Gleb Flishtinsky , lighting and video designer, have contributed to the production's success in visible ways: the former's costumes, whose aesthetic is faithful to the classic characterization of the characters, but with a cartoonish touch. From the third scene onwards, Flishtinsky's videos begin to become part of the production and, I would say, are the key to its success: in them we see animations that help us to understand the story and to set it: the suffering of the Tsarina and her son in the barrel; the hunting of the falcon and the release of the swan, which, after becoming a princess, appears surrounded by a colorful landscape; the moving appearance of the city of Ledenets; or the Tsar's court table and the bumblebee that stings the Tsarina's evil witch sisters. All this action takes place in Guidon's imagination and is projected onto a panel that only he can enter through, under the watchful eye of his mother. At the end of the play, the Swan Princess is freed, becoming a real person, a girl just like Guidon. The Tsar, the sisters, and the court appear in the real world: they are Guidon's father and his friends, who have come to help father and son get to know each other. But in the end, madness and confusion take hold of everyone present, and poor Guidon has an anxiety attack and punches the wall, invoking the fairy-tale world, as it is the only place where he is happy and safe, much to his mother's dispair.

Karel Mark Chichon was scheduled to conduct the Teatro Real Orchestra , but for health reasons he had to be replaced by the Israeli conductor Ouri Bronchti, musical assistant at La Monnaie in Brussels and to Alain Altinoglu, who conducted the production's premiere in the Belgian capital. Bronchti made the orchestra fulfilled and recreated the magical world enclosed in Korsakov's score. The interludes were inspired, with special mention of the horns and violins. As for the Teatro Real Choir , always professional under the direction of José Luis Basso , they had to deal with the challenge of singing competently in Russian and with the always complicated movements in Tcherniakov's productions. There were moments when the chorus sang on stage, but at other times the voices seemed to come from offstage, even if people were there, as if Guidon's mind were narrating the story.

Svetlana Aksenova is completely devoted to the production, convincing as a concerned mother and caregiver to her son, with a nice singing. The role of Guidon has beautiful music and requieres a voice that shines like the character. After having sung Lenski in Tchaikovsky's Onegin two months ago, Bogdan Volkov now takes on Guidon with his lyrical voice. Volkov doesn't have the greatest volume, but his effort is notable, and his lyrical-toned voice and devotion to the character align with Tcherniakov's vision of the autistic Guidon.

Of the rest of the cast, Ante Jerkunica was a well sung Tsar Saltan, Carole Wilson as the wicked Babarikha is the best of the cast, with outstanding bass, Nina Minasyan was a Swan Princess with a beautiful voice, and the Spanish tenor Alejandro del Cerro as a well-sung messenger.

Opportunities to see works like this are rare, and it's a good thing that in eight years, two Rimsky-Korsakov operas have been performed at the Real. Judging by the comments heard from the audience, even those ones who had reservations about Tcherniakov's staging, wer delighted and gave applause to almost the entire cast, especially Aksenova and Volkov.