Madrid, October 3, 2025.

This is David Afkham's final season as principal conductor of the Spanish National Orchestra. A fruitful period in which this orchestra has become a local benchmark for the Germanic repertoire: its renditions of Bruckner, Mahler, and Wagner bear witness to this. The first title of the ONE's 2025-2026 season is one of the most important operas not only of the 20th century but of all time: Alban Berg's Wozzeck.

Under Arnold Schoenberg, the Second Viennese School challenged tonality at the beginning of the last century, with Alban Berg and Anton Webern as his most accomplished disciples. Berg composed two operas: one, Wozzeck, and the other, Lulu (which he never finished), both inspired by German theatrical masterpieces about tragic outsiders from society. In these operas, Berg successfully balanced theatrical stories with innovative music, while also featuring nods to tradition, taking atonal music to a more human and romantic level than his teacher Schoenberg did. Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, Berg saw a performance of Georg Büchner's play Wozzeck and was immediately struck by the inspiration for an opera. Büchner's work is based on a true story: at the beginning of the 19th century, a soldier, Johann Christian Woyzeck, murdered his partner for being constantly unfaithful and was executed for it. However, his broken mental state (he suffered from schizophrenia) was studied (in a pioneering way at the time), in a case that shocked German society at the time. Both Büchner in his work and Berg in his music dealt with the drama of Woyzeck (whom Berg called Wozzeck), a man with disorders bordering on madness, who is part of an impoverished and exploited working class, living in a vicious cycle of poverty. Berg took ten years to complete this project, and its premiere in Berlin in 1925 was a musical event in a Post-WWI Germany filled with impoverished people like its protagonist, who would entrust themselves to a "Wozzeckian" leader who a decade later would consider this work "degenerate" and ban it during his twelve years of terror.

Yet, despite everything, time has established Wozzeck in the repertoire for its musical and theatrical power: a stark portrait of the humble working class through the personal tragedy of this impoverished soldier. This story is accompanied by powerful music, requiring a huge orchestra, with orchestral richness, evocative and striking musical interludes, as well as other passages of great beauty; it conveys the anxiety of the protagonist and his surroundings. The music is atonal and twelve-tone, yet incorporates traditional elements such as the leitmotif, with themes that will be heard together in the powerful final orchestral interlude, as a summary of the protagonist's sad life. Its impact can only flow completely in the theater. One leaves Wozzeck overwhelmed, gutted, shaken, but not indifferent.

David Afkham has done it again: his reading of the work was stunning. Each section of the Spanish National Orchestra sounded as dark, tragic, gloomy, and haunting as the score itself. The orchestra's interpretation of the musical interludes was exquisite, striking, and evocative, conveying their beauty and impact. A case in point is the brief and intense interlude between Scenes 2 and 3 of Act III, after Wozzeck kills Marie, which reflects his frantic escape. A brief piece divided into two parts, one stronger than the other. The ONE performed it so powerfully, from the brief opening by the brass to the final tutti, in forte and agonizingly prolonged, that some people even covered their ears. The rendition of the final interlude was equally striking, followed by a rapid but sad and emotional version of the final chords and woodwind, which foreshadow the tragic fate of the now orphaned son. The Chorus of the Spanish National Orchestra sounds well in its brief interventions: the male chorus managed to make its Act II performance sound like choral folk music in Scene 4 and ghostly in Scene 5.

Martin Winkler is a well-known singer in Madrid, having recently performed extensively in the capital: Alberich in the Ring (2021,2022), Waldner in Arabella, and Shostakovich's The Nose, both in 2023. Now he takes on a role in which, despite the maturity in his voice and his grotesque guttural timbre, he is masterful as an actor. His Wozzeck is that of a completely mad man, oblivious to reality, the target of ridicule, a human wreck, who inspires compassion, but is also capable of aggression.

Lise Lindström, on the other hand, was the star of the cast with her well-sung Marie. Her voice is still resilient despite of the orchestra behind her and the repertoire she usually sings. Even so, she delivered impressive high notes and was a superb actress, haunting when she recites the Bible passage in the third act.

Jürgen Sacher was a well-sung Captain, but overpowered by the orchestra. Stephen Milling sang the role of the Doctor with his beautiful bass voice, but also had moments when the orchestra overpowered him too. Tansel Akzeybek, on the other hand , was a well-sung, youthful, Andres. Rodrigo Garull was a sung Drum Major with an attractive, dramatic voice. Solgerd Isalv was a little more discrete as Margret, although her voice has beautiful low notes. The rest of the supporting cast and the girls' chorus were convincing in their roles. Special mention goes to the boy Jairo Somolinos , who played the unfortunate son of Wozzeck and Marie.

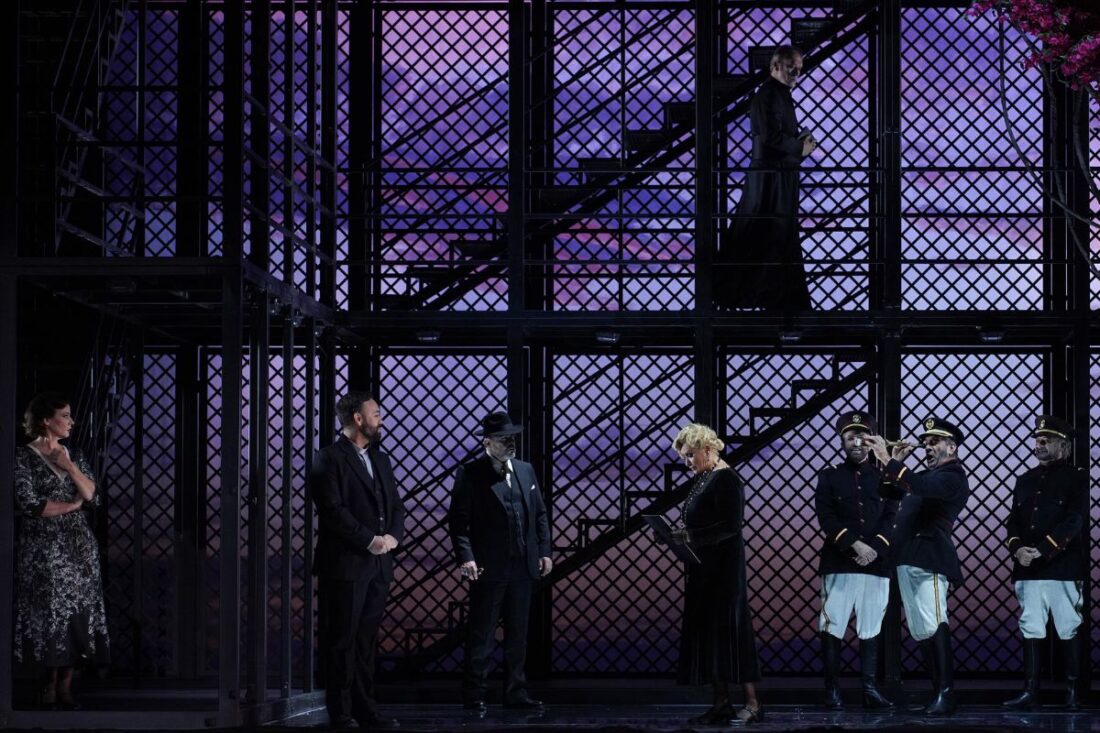

The concert performance had a scenic concept by Susana Gómez, which greatly aided the performance: the play of lighting created an atmosphere as gloomy as the story. In the Marie's death scene and Wozzeck's subsequent escape, the room was lit in a deep red, as well as during the final interlude, when the hall was lit in a turquoise green that increased the feeling of sadness. A barber's chair was used not only for the opening scene, but also as a bed for Wozzeck's son and where the soprano lies for a while after Marie's death.

Wozzeck is not an easy opera, and there were several dropouts during the performance. But those who stayed until the end, the majority, enthusiastically applauded the artists after the ending of the show. A remarkable evening of opera, in which the audience enjoyed the quality of the music and ended moved after an hour and a half of stark realism. Even today, among the most disadvantaged in every society all over the world, there are still Wozzecks and Maries struggling to survive. Berg was a genius, and this proves it.